The curtain lifts on a dim stage. A single banner hangs overhead, heavy with color and symbol. A drumbeat starts: slow, insistent. An actor steps into the light wearing a uniform that is not quite accurate, but feels truer than a photograph. The audience leans forward. In that moment, the theater is no longer a room. It is a battlefield. A chapel. A courtroom. A weapon.

Propaganda in wartime theater is not just posters and slogans brought to life. It is the art of shaping feeling with story, costume, and light until an audience walks out thinking a little less freely than when it walked in. Or, occasionally, a little more. It can stiffen a spine, close a mind, or crack open a doubt. It turns the stage into a printing press for belief.

What wartime propaganda theater really does

If you strip away the flags, the speeches, and the patriotic anthems, wartime propaganda theater does one thing: it edits reality so that one version of truth feels inevitable.

It does this by choreographing emotion. By turning enemy soldiers into shadows. By painting “our” dead as martyrs and “their” dead as statistics. By hiding the smell of blood under the perfume of sacrifice. It simplifies chaos into a story that fits in the space between curtain up and curtain down.

Sometimes that story is loud and obvious: heroic generals, noble factory workers, a wicked invader booed on cue. Sometimes it is nearly invisible: a comedy where the enemy is always the butt of the joke, an intimate drama where doubt is mocked and certainty rewarded. Either way, wartime theater propaganda is not just text. It is scenography, blocking, timing, silence. The entire visual and emotional design is enlisted.

Propaganda in theater is not only what the characters say. It is what the lights do, what the costumes suggest, and what the audience is quietly trained to feel together.

So if you work with theater, immersive performance, or visual storytelling, you cannot treat wartime propaganda as an odd historical footnote. It is a manual on how power uses space, sound, and image to guide collective emotion.

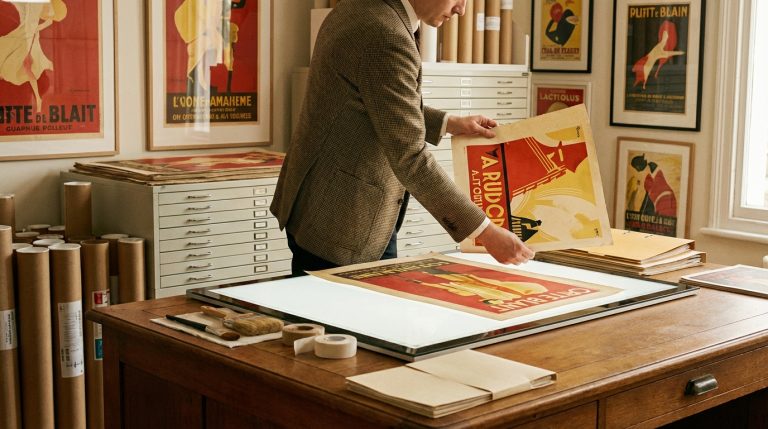

How propaganda moves from poster to stage

Theater is perfect for wartime propaganda because it works in the same language as war itself: bodies in space, tension over time, crowds responding as one. A poster can shout; a play can seduce.

- Posters broadcast a message outward. Theater traps you inside a message.

- Radio enters your home. Theater gathers you into a shared ritual.

- Film can be paused. Live theater carries you forward on live breath and risk.

The propagandist understands this very well. In wartime, scripts become policy in disguise. Set designers become cartographers of ideology. Directors become choreographers of consent.

The stage as a controlled reality

A wartime propaganda play is a curated little universe. Every element is tuned to remove uncertainty. War itself is chaotic, full of contradiction and moral grey. The propagandistic stage trims that away.

Think of the stage as a diorama of belief:

| Element | Propaganda Function |

|---|---|

| Set design | Defines who “belongs” and who is “intruding”; signals what spaces are sacred or threatened. |

| Costume | Turns citizens into archetypes: hero, traitor, worker, mother, enemy. |

| Lighting | Bathes the “just” side in warmth, frames the “enemy” in distortion, smoke, or shadow. |

| Blocking | Shows who commands the space and who gets pushed to its edges. |

| Sound & music | Regulates emotion; attaches melodies to loyalty and dissonance to doubt. |

In wartime propaganda theater, the set is not a backdrop. It is the argument, made physical.

When you stand inside such a space, whether as audience or performer, you feel where you are allowed to stand morally. That is part of its power.

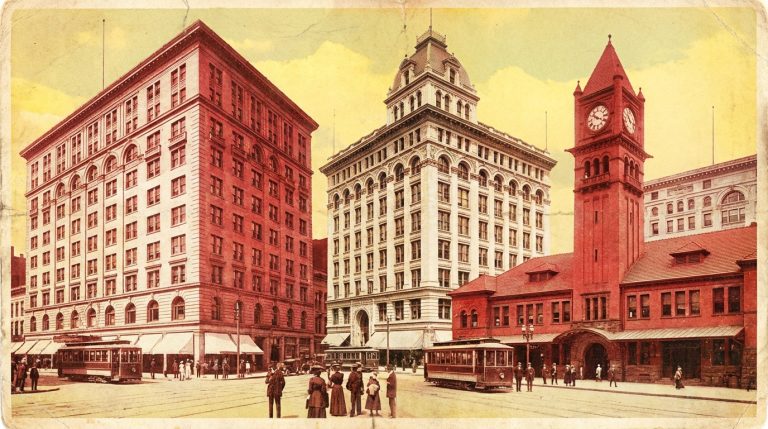

World War I: patriotic stages and the birth of total war theater

As the First World War pulled entire societies into conflict, theater houses became informal recruiting halls and morale engines. The proscenium arch framed not just plays, but national narratives about duty and sacrifice.

British and French stages: morale, sacrifice, and sanitization

In Britain and France, many theaters turned patriotic almost overnight. Scripts were hastily written to show cheerful volunteers, stoic nurses, and the noble endurance of families left behind. The trenches appeared on stage, but tidied up.

The set design often leaned on familiar domestic interiors: a kitchen, a parlor, a village square. Costumes gave you clean uniforms, barely smudged, with brass that glinted. Lighting smoothed away the mud and horror that newspapers could not fully show.

The most powerful lie on these stages was often not what was added, but what was removed: fear, boredom, disillusionment, and the breakdown of faith.

There were plays that stirred genuine solidarity and others that felt like government leaflets with better costumes. In both cases, the audience saw a version of war that could be carried home without shattering.

Germany and Austria-Hungary: mythic framing

On the other side, German and Austro-Hungarian theaters used myth and tragedy to frame their war as a historic trial of the nation. Classical references, monumental arches, and banners created a sense that the present conflict was tied to ancient heroism.

The design language grew heavy: large, stone-like set pieces, stark banners with bold symbols, rigid formations of actors. Space became architecture of inevitability: war as fate, not policy.

Early resistance: cracks in the painted scenery

Even in this climate, some theater practitioners quietly resisted. They wrote plays that emphasized the physical cost of war, or that hinted at incompetence in leadership. Yet these tended to be smaller productions, often censored or pressured.

Visually, resistance showed up in:

– Sets that looked bare, exposing fragility instead of grandeur.

– Costumes that revealed physical damage and exhaustion, not just medals.

– Lighting that lingered on absence: an empty chair, a vacant doorway, a darkened window.

These design choices pushed against the smooth surface of state-approved narratives. They did not always succeed in reaching wide audiences, but they left a trace, especially among later anti-war artists.

World War II: theater enlisted on all fronts

World War II expanded propaganda far beyond posters and cinema. Theater, though sometimes overshadowed by film, became a quiet but persistent instrument in many countries.

Nazi Germany: theater as architecture of ideology

Under the Third Reich, theater was monitored, controlled, and shaped to serve the regime. Classical plays were reinterpreted to mirror Nazi values, while new works glorified racial myth and national destiny.

Set and stagecraft followed the same visual grammar as Nazi rallies: symmetry, monumental scale, strong verticals. Spaces often felt rigid and ceremonial.

Costume design played heavily with uniforms and “ideal” bodies. Heroes tended to occupy center stage, upright and framed by clean lines. Those marked as undesirable or enemy were pushed to shadows or distorted spaces.

Lighting here was brutal in its clarity. Harsh key lights sculpted faces into relief. Contrast was high. Nuance was not welcome.

The Nazi stage trained the eye to love order and purity, and to fear anything that broke the pattern.

For a modern designer, looking at this work is uncomfortable, but useful. It is a study in how visual clarity can be misused to flatten reality into ideology.

Soviet Union: agitprop and the mobile stage

The Soviet tradition of agitprop theater began earlier, but wartime sharpened its role. Performers took skits, songs, and short plays to factories, collective farms, and front lines. Stages were improvised: truck beds, courtyards, clearing in the woods.

The set here was often nothing more than a banner and a few symbolic objects: a hammer, a rifle, a flag. The design relied on strong graphic shapes and simplified color palettes, usually red, black, white, and military tones.

Agitprop favored direct address. Actors spoke to the audience, not just to each other. This broke the frame and turned spectators into participants.

Sound was urgent: chants, rhythms, call-and-response slogans. The line between rehearsal and rally almost vanished.

From a design perspective, this was propaganda stripped to its essentials:

– Minimal scenery, maximum symbol.

– Clear spatial hierarchies: the speaker elevated, the crowd below.

– Visual repetition: the same slogans and symbols appearing across locations, creating familiarity and comfort with the ideology.

Allied countries: reassurance and righteous anger

In Britain and the United States, wartime theater genres ranged from patriotic dramas to light comedies that offered escape, yet many productions quietly carried messages.

Some plays framed the conflict as a moral struggle against tyranny, using familiar domestic sets threatened by offstage violence. Others showed factories and shipyards as heroic settings, turning industrial spaces into stages of valor.

Designers often balanced authenticity with legibility. A too-accurate factory might feel grim; a slightly idealized one could project pride and unity. Neutral, sturdy materials, warm light, and well-ordered props nudged audiences toward seeing war work as meaningful, not crushing.

Comedy played its own role. Comic depictions of enemy leaders and soldiers ran the risk of trivializing the threat, but also served to keep fear from overwhelming the home front. The line between healthy relief and crude dehumanization was not always respected.

Occupied stages: theater under censorship and surveillance

In occupied territories, the stage could become a careful game. Regimes demanded loyalty. Resistance movements watched for betrayal. Audiences sought both survival and truth.

Vichy France, Poland, and others: coded resistance

Some theater artists learned to speak in layers. An officially acceptable play might hide subversive subtext in casting, staging, or emphasis.

Set design became a secret code:

– A cracked wall in a domestic set that looked a little too much like a shattered border.

– A broken statue that resembled toppled authority.

– A recurring visual motif, such as a specific flower or object, recognized by local audiences as a symbol of resistance.

Lighting choices emphasized the “wrong” parts of the text, lingering on lines that guilted collaboration or praised blind loyalty, turning them into quiet criticism.

At the same time, open propaganda performances celebrated occupiers, framed resistance as criminal, and portrayed submission as wisdom. These usually favored polished, classical aesthetics: grand architecture, richly detailed costumes, and stable, balanced compositions that implied a restored “order.”

In occupied theaters, propaganda and resistance often shared the same stage. The difference lived in what the design whispered between the lines.

Post-war memory: how theater rewrites the story of conflict

War does not end when the guns fall silent. It continues in memory. Theater becomes a way to revisit, justify, question, or mourn what was done. Propaganda does not vanish here; it just mutates.

Victors, victims, and the politics of set design

Post-war plays often present narratives of heroism or victimhood. The stage design declares which one is foregrounded.

In some countries, sets filled with rubble, grey walls, and empty windows told a story of suffering and endurance. Others showed reconstructed homes, bright colors, and orderly streets to emphasize renewal and national strength.

The question is: what or who is missing?

– No depiction of war crimes.

– No visible trauma on returning soldiers.

– No faces of defeated or marginalized groups.

Silence in design is as political as any banner. When certain histories never appear in the stage picture, they slowly fade from shared memory.

Trials and tribunals as theater

Real war crimes tribunals have often been described as theatrical, and they are. Stages, sightlines, costumes (uniforms, robes), and scripts (testimonies) all matter. When theater artists recreate or respond to these moments, they are not neutral.

A production about a trial can either reinforce official narratives or question them. A minimalist, stripped-down set might highlight human voices and moral conflict. A more literal, detailed courtroom might emphasize legality and procedure.

The danger lies in spectacle. When the horror of war becomes visually “beautiful” on stage, the audience can become aesthetes of suffering rather than witnesses.

The Cold War and beyond: ideology on and off the proscenium

During the Cold War, propaganda in theater did not disappear; it diversified. Some states sponsored theater that defended their systems, while independent groups experimented with forms that resisted any simple ideological packaging.

State-sponsored narratives

In both Eastern and Western blocs, subsidized theaters sometimes carried implicit expectations:

– Praise national values.

– Criticize the enemy system.

– Soften internal contradictions.

On stage, you could see this in the spatial hierarchies: authority figures granted large, well-lit areas; dissenters pushed to cramped or fragmentary spaces. The comic relief character who questions the system is allowed humor, but not real change.

Designers who tried to push back did so through fragmentation: non-realistic sets, disjointed props, lighting that never settled into reassuring warmth. These methods made it harder to turn a play into a clean propaganda product, because the space itself felt unstable.

Political theater movements

Many theater makers used the stage to attack propaganda itself. Brechtian techniques, for example, aimed to prevent emotional hypnosis. Signs on stage, exposed lighting rigs, visible scene changes: all tools to remind the audience that it was watching a construction, not reality.

From a design perspective, this is a deliberate refusal of illusion. The set says: “Look. This is built. So are your beliefs.”

Yet even anti-propaganda theater can slip into another kind of propaganda, promoting its own certainties. When every villain wears the same symbolic color or stands in the same oppressive architecture, the piece risks turning complex issues into a new set of slogans.

Propaganda is not only what supports the state. It can be any stage picture that insists there is only one way to feel about what you are seeing.

Immersive and site-specific wartime propaganda

When theater steps off the stage and into streets, bunkers, warehouses, or VR headsets, propaganda does not lose force. It gains intimacy.

Reenactments and heritage shows

War reenactments and heritage performances can be rich educational tools. They can also quietly propagate myths.

Set design in these contexts is often environmental: fields, historical buildings, reconstructed trenches. Accuracy in uniforms, weapons, and vehicles may be high, but accuracy in emotional framing can be selective.

Consider two different immersive experiences about the same battle:

– One highlights bravery, tactics, and camaraderie. The sound design amplifies commands, cheering, stirring music.

– Another stresses terror, confusion, and moral doubt. Sound is chaotic and disjointed. Lighting is disorienting, with sudden darkness.

Both might be “accurate” in detail, but their design choices tell very different stories about what war means. The first risks becoming a recruitment poster for nostalgia. The second interrupts that temptation.

National museums and memorial theaters

Many countries use theatrical installations in museums and memorials. Projected images, sculptural sets, guided tours with actors. These spaces can be deeply moving, but they are also curated belief factories.

Designers decide:

– Which events receive a full immersive room, and which get a small caption.

– Whose letters are read aloud by actors.

– How tall the walls are, how loud the guns sound, how long visitors must sit with each image.

This is propaganda in a softened form: shaping national memory with texture, scale, and pacing. The intent might be education, mourning, or pride, but the effect is still directional.

Recognizing propaganda tools in theatrical design

If you work in set design, lighting, or immersive space, you need a practical eye for when your tools slip into propaganda.

Common visual techniques that shape belief

- Binary color coding: one side in clean, harmonious colors; the other in discordant or dirty tones.

- Spatial moral mapping: the “good” characters always center stage and elevated; the “bad” always sidelined or in shadow.

- Symbol overload: flags, insignia, and slogans repeated until they become visual wallpaper, accepted without question.

- Heroic perspective: camera-style staging that often looks “up” at authority figures and “down” at the enemy or common people.

- Rhythmic control: lighting cues and sound swells that push the audience to clap, shout, or weep on cue, standardizing emotional response.

None of these techniques is inherently unethical. They are part of any theatrical vocabulary. The ethical problem appears when they are used to shut down doubt and flatten complexity.

The ethical questions a designer should ask

Before committing to a wartime or political project, it helps to stand in the imagined space in your mind and interrogate it.

Who is allowed to appear in this space, and who is missing? Where can each character stand, and where can they never go?

Questions to sit with:

– Are you portraying the enemy as human at all, or only as caricature?

– Is suffering aestheticized to the point of beauty that distracts from its weight?

– Does the design leave any room for ambiguity, or does it lock the audience into a single response?

– Are you reinforcing a myth that comforts the victors while erasing others’ pain?

– Is there pressure, from funders or partners, to “soften” certain truths?

Sometimes the honest answer may be uncomfortable. Propaganda is not only created by authoritarian regimes. Liberal democracies, activist groups, and commercial producers all shape narratives in self-serving ways. As an artist, you have some responsibility for the space you help construct.

Using theatrical craft to resist propaganda

If propaganda closes down thought, theater can also create the opposite: conditions where questioning feels possible.

Designing for complexity, not neutrality

Neutrality is often an illusion, but complexity is a reachable goal. You can build spaces that show multiple truths colliding without prescribing one correct conclusion.

Some methods:

– Mixed visual codes: combining heroic iconography with signs of decay, showing both pride and cost in the same frame.

– Shared spaces: placing “enemy” and “ally” characters in the same physical zones, breaking rigid spatial segregation.

– Exposed artifice: letting the audience see some of the machinery of the show, reminding them that what they see is constructed.

– Interruptions: moments where sound or light cuts out, leaving room for uncomfortable quiet, rather than carrying emotion in a single direction.

None of this requires abandoning aesthetic rigor. On the contrary, it demands very precise control. Messy design does not guarantee honest politics.

Audience agency inside the design

Immersive and interactive work offers a particular chance to counter propagandistic tendencies. When spectators move, choose, and witness from varied angles, the narrative becomes less fixed.

As a designer, you might:

– Create multiple vantage points where different audiences see different aspects of the same scene.

– Allow participants to follow different characters, each carrying incomplete information.

– Design spaces where artifacts and documents contradict the spoken narrative, inviting doubt.

This is not always comfortable. Some spectators prefer to be guided clearly. Yet this discomfort can be more ethical than the false ease of a perfectly coherent propaganda story.

Why wartime propaganda theater still matters to designers now

You could treat this topic as historical curiosity. Old photos of patriotic stages, crude slogans, rigid poses. Safe distance. That would be a mistake.

Every time a country faces conflict, internal or external, theater gets pulled toward the front line of narrative again. State sponsors, private patrons, activist collectives: all seek images that confirm their version of events.

If you work in theater or immersive arts, you will eventually be asked to build someone else’s story of war. The question is not if, but how you respond.

Wartime propaganda in theater is not only about censorship and authoritarian control. It is about the subtle, seductive pleasure of a simple story, beautifully rendered. The glow of unity in a dark room. The relief of certainty when the world outside feels chaotic.

As artists and designers, we shape those rooms. We decide how high the walls are, how narrow the doors, how many exits thought can find.

The history of propaganda in wartime theater is a catalogue of techniques, mistakes, brilliance pressed into the service of harmful causes, and occasional acts of resistance smuggled in visual detail. Learning from it does not mean avoiding strong images or powerful emotion. It means treating every banner, beam of light, and scenic choice as part of a moral architecture, not just an aesthetic one.

The stage will continue to be used to rally, to justify, to mourn, and to question. Our craft can either make propaganda sharper, or make audiences sharper. The tools are the same. The intention, and the design of the experience, are what change.