The stage lights are still warming. Dust hangs in the air like faint constellations. A single chair. A discarded glove. The echo of a line spoken a hundred years ago, still lodged in the wood. Theater remembers. Even when the programs fade, even when the photos yellow, the space holds the imprint of bodies that stood there and refused to be quiet. Many of those bodies belonged to women who had to fight simply to be seen, much less celebrated.

Here is the short version, before we wander through centuries and footlights: women did not “join” theater history late. They built it. From the first playwright whose words survive in full, to moguls who owned theaters, to actresses who turned their fame into artistic control, women have shaped what the stage looks like, how it sounds, and who is allowed to stand upon it. They pushed for realism, for poetry, for protest, for joy. They directed when they were expected to smile. They designed when they were expected to wear the costumes, not sketch them. If you love theater that feels alive, precise, and deeply human, you are already living inside the work of these women.

The long shadow of forgotten names

Walk into almost any theater building and look at the brass plaques. You will see a lot of men carved into metal. Directors. Playwrights. Patrons. The story that follows from those walls suggests that women are late arrivals, special mentions, exceptions.

That story is wrong.

Women have always been in the room; history just kept pointing the spotlight elsewhere.

Some names have survived in bold print: Aphra Behn, Sarah Bernhardt, Lorraine Hansberry. Others float at the edges of programs and archives: bookkeepers, seamstresses, scenic artists who never saw their names above the title. For this article, I will stay with the women whose careers leave clearer footprints, while remembering that every famous name stands on an invisible chorus.

After this first section, you will find the only list in this piece, a quick map of some figures we will meet. Keep it close as you read, like a miniature cast sheet for a very long-running production.

A brief cast of recurring names

- Aphra Behn (1640-1689): English playwright and former spy, one of the first women in Europe to live by her pen.

- Sarah Siddons (1755-1831): Tragic actress who turned performance into high art and personal power.

- Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923): International star, theater owner, and relentless self-mythologiser.

- Loie Fuller (1862-1928): Lighting and movement experimenter who changed stage visual language.

- Hallie Flanagan (1890-1969): Head of the U.S. Federal Theatre Project.

- Cheryl Crawford (1902-1986): Producer and co-founder of the Group Theatre, the Actors Studio, and ANTA.

- Tharon Musser (1925-2009): Lighting designer who helped move Broadway into the computer age.

- Robin Wagner (1933-2024) appears often in design histories; here, we center women who worked around him.

- Julie Taymor (b. 1952): Director-designer whose “The Lion King” changed the visual expectations of commercial theater.

- Catherine Martin (b. 1965): Designer whose theatrical instincts spill across stage and screen.

This is a thin slice, but it can orient us as we step, time by time, into different rehearsal rooms.

Before the velvet curtain: the first woman with a quill

Picture London in the late 1600s. The playhouses smell of oranges and sweat and candle smoke. Restoration comedy is loud, sharp, lewd, exquisitely dressed. Men write most of it. Men run the companies. Men play the serious roles. Women are onstage now, but watched like curiosities.

Into this chaos steps Aphra Behn.

She had already been a spy. She had already seen political intrigue close-up. Now she turned to writing to make a living, not as a hobby. It was survival. That urgency pulses through her plays. “The Rover,” perhaps her best known work, is soaked in sex, power, and disguise. It is messy and human. That is the point.

Behn did something radical: she treated women’s desire, wit, and rage as worthy of stage time.

She wrote quickly, under pressure, balancing crowd-pleasing plots with a fierce sense of self. Morality campaigners attacked her work as indecent. They did not scare her off. Behn proved that a woman could be both commercially successful and unapologetically herself. For later playwrights, she is less a quaint historical note and more a quiet permission slip: you are allowed to sign your name to what you write.

The physical spaces around her were still lit by candles. The sets were sliding flats. Yet inside those constraints, she carved out psychological rooms where women were clever and complicated, not ornaments.

Actresses who bent the audience to their will

Long before cinema close-ups, there were actresses whose faces carried whole worlds to the back row.

Sarah Siddons in the late 18th century was one of these. She played Lady Macbeth as a woman driven by terrifying clarity instead of mere villainy. People fainted watching her. That says as much about her command of presence as it does about audiences unaccustomed to such acute psychological detail from a woman on stage.

Siddons did not just act. She managed her image. She navigated the social code of her era with care. Her portraits show her in heroic poses, often more akin to statesmen than to coquettes. She treated her career as both art and architecture, building a persona strong enough to resist moral panic.

A century later, Sarah Bernhardt would stretch this shape even further. If Siddons was a sculpted column, Bernhardt was a plume of fire. She toured the world, owned a theater in Paris, and stepped into roles that underlined her refusal to be confined. Her Hamlet and other “trouser roles” put her inside stories written for men and turned them inside out.

Bernhardt understood stage picture like a designer. She cared where her body was in relation to light, fabric, and architecture. Photographs of her in swirling gowns and stiff armor feel almost like costume sketches that someone forgot to flatten back onto paper.

What links Siddons and Bernhardt is not just talent, but a strategic hunger for control over space, narrative, and self-image.

They showed future performers that being an actress did not have to mean surrendering authorship of your own life.

Women who redrew the stage picture

By the late 19th century, theater was changing visually. Gaslight shifted to electric light. Painted flats started giving way to more dimensional sets. In this period, several women stepped forward as visual inventors, not just performers.

Loie Fuller is often called a dancer, but for designers, she is something else: a moving light experiment wrapped in fabric. Imagine a near-dark stage. A figure appears, draped in silk that catches colored light like water. She spins, the fabric unfolds, becomes wings, a flower, a flame. The light does not simply illuminate her. It sculpts her.

Fuller worked obsessively with lenses, color media, mirrors. She patented lighting devices. She collaborated with chemists. She treated the stage as a laboratory and her own body as the main instrument. This is not a “side note” to history; it marks a shift in how artists thought about light as more than visibility.

Fuller dragged lighting out of the background and made it a central dramatic partner.

That shift opens the door to later lighting designers, many of them women, who claim the booth as a creative seat, not just a technical one.

The story of scenic design is often framed around male names, especially in Broadway lore, but behind and around those names are women who shaped aesthetics in quieter ways. Scenic painters, model builders, and prop masters rarely see their names on posters. Yet they are deeply involved in the spirits of productions.

To keep this grounded, look at a more documented figure: Tharon Musser, who would arrive in the mid-20th century but stands in a direct line from Fuller. Musser lit shows like “A Chorus Line” and “Dreamgirls,” helping to define a sleek, muscular quality of light that could hold both chorus kicks and intimate confessions. She was among the first to use computer-controlled lighting on Broadway, not as a novelty, but as a precise instrument.

The shift matters less as a tech history note and more because it changed what was possible visually. Rapid, musical cues. Environments that breathe with the cast. The geometry of light becoming architecture in its own right.

| Figure | Primary Field | Key Contribution to Theatrical Space |

|---|---|---|

| Loie Fuller | Movement & Light Experimentation | Turned light and fabric into moving sculpture, inspired modern stage lighting concepts. |

| Tharon Musser | Lighting Design | Pioneered computer-controlled lighting on Broadway, refining kinetic, musical cueing. |

| Julie Taymor | Directing & Design | Integrated masks, puppetry, and architecture into unified visual storytelling. |

| Catherine Martin | Design & Art Direction | Brought theatrical scale and detailing into film, bridging stage instincts with cinema. |

When you look at these names side by side, you can see a through-line: women not only occupying roles but stretching what those roles could do visually.

Women as producers and structural architects

Behind nearly every revolution in theatrical aesthetics sits a quieter revolution in who holds the purse strings and scheduling power. A beautiful set sketch is useless if someone with authority will not budget it, program it, build it.

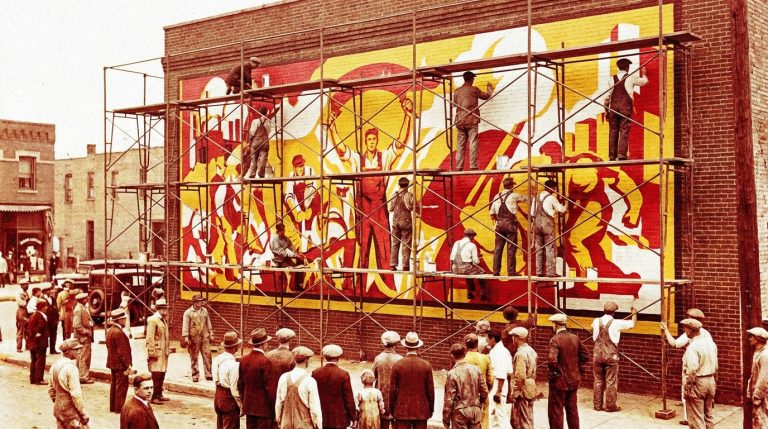

In the 1930s United States, Hallie Flanagan headed the Federal Theatre Project, a government-funded effort to keep theater workers employed and audiences engaged during economic crisis. Her work was national in scope: “Living Newspapers,” large-scale regional projects, experimental forms. She treated theater as a public necessity, not a luxury.

Flanagan did not simply commission plays; she shaped a model where theater could be investigative, topical, and accessible. That kind of system-building is as creative as any script.

A bit later, Cheryl Crawford emerges as a producer in New York who participated in founding three major entities: the Group Theatre, the Actors Studio, and the American National Theatre and Academy (ANTA). She wrangled schedules, money, and egos while pushing for work that valued ensemble, depth of acting, and strong design choices. Her influence is structural. Without someone like Crawford willing to endure the strain of producing difficult work, many iconic 20th-century productions would not exist.

Where designers redraw the stage picture, producers like Flanagan and Crawford redraw the conditions under which that picture can exist at all.

For anyone thinking about immersive or site-based work today, these histories of women who engineered systems are crucial. Your wild light and sound concepts live or die on who can protect them structurally.

Voices on the page: playwrights who cracked the form open

Text is not neutral. The way a play is written dictates what kind of world appears onstage. When women write plays, they do not simply add more female characters. They often alter the entire architecture of the story.

Henrik Ibsen’s debt, and then women writing themselves

For a long time, theater histories laud Ibsen and Chekhov for psychological realism and “strong women.” Nora slamming the door in “A Doll’s House” is treated as a pivot. Yet the evolution does not stop with a male writer giving a woman character a complex arc.

Enter women whose own lives and communities sit at the center of their storytelling.

Lorraine Hansberry wrote “A Raisin in the Sun” at 28. The play is crisp and quiet on the surface: a family in a cramped Chicago apartment, plans for a better life, each person hemmed in by racism, class, and gender expectations. Yet the structure is as sharp as any Greek tragedy. Each character collides not just with fate but with the strict geometry of the room itself.

Hansberry was the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway. That fact is often repeated. Less repeated is how visually aware her scripts are. The apartment is not just backdrop. It is pressure, history, and magnet. For set designers, working on her play is less about decoration and more about showing the invisible forces that sit on every chair and window.

Caryl Churchill, working in Britain, bent form further. “Top Girls” layers overlapping dialogue and jumps in time. “Cloud Nine” toys with gender and casting in ways that directly ask an audience to question fixed identity. Her stage directions are elegantly lean, inviting directors and designers to sharpen their own imaginations rather than hiding behind visual clutter.

Hansberry and Churchill do not just give women more lines; they rewire how lines, silence, and space behave around them.

Their work sets a precedent for plays that allow sets and lighting to think, not just illustrate.

Language as architecture: Angelou, Fornes, Parks, Kane

Several playwrights use language so physically that it might as well be lumber and fabric.

María Irene Fornes wrote plays that feel like rooms you slowly discover blindfolded. Her dialogue is often simple, yet charged, and her stage directions are spare puzzles. She directed many of her own works, rehearsing intensely, unlocking the rhythm of pauses and glances. Designers working with Fornes often speak of needing to “listen” to the text with their eyes, because nothing is ornamental. Every chair, every wall, carries weight.

Suzan-Lori Parks pulls history and myth into looping structures. In “Topdog/Underdog,” two brothers in a small room become a universe of power, role-playing, race, and performance itself. Her scripts sometimes include repetitions that feel like a drumbeat. For set design, the constraint of space becomes a challenge: how to let a tiny physical area hold enormous spiritual and historical density without overloading it.

Sarah Kane, in late 20th-century Britain, writes plays where violence and tenderness collide in stark frames. The stage directions for “4.48 Psychosis” read more like a score than a traditional script. There are no fixed characters. No clear locations. Just text, like fragments of internal weather. Directors and designers taking on Kane are not “illustrating” but making decisive cuts through ambiguity, choosing spatial metaphors for mental states.

These playwrights insist that stage space is not neutral floor; it is an extension of thought and feeling.

For contemporary immersive makers, that idea is foundational. If you invite audiences to walk through a story, every corridor, ceiling height, and texture becomes “dialogue.”

Directors who sculpted experience

Directing is often described as interpretation, but many women directors have treated it more like world-building. Every gesture, every prop, every shaft of light is chosen to tune the emotional temperature of the room.

From Margaret Webster to JoAnne Akalaitis

Margaret Webster, active in the mid-20th century, staged Shakespeare with clarity and a refusal to condescend to audiences. Her “Othello” with Paul Robeson in 1943 was a charged event: a Black Othello opposite a white Desdemona on Broadway, in a time seamed with racist fear. Webster’s visual decisions around proximity, touch, and space did not dilute that charge. She leaned into it.

JoAnne Akalaitis, later associated with Mabou Mines, embraced experimental forms. Her work draws on collage, media, and strong visual composition. She often engaged with texts in ways that foreground the body in space. In those rooms, actors do not simply “deliver lines.” They become part of a carefully arranged image, shifting across sculptural environments.

Both directors demonstrate different paths away from the single-author myth. Theater is built by many hands, yet the director can be the one who listens to all of those voices and arranges them into coherent visual and emotional progress.

Julie Taymor and the visible puppet strings

Julie Taymor is perhaps the most visible female director-designer in global commercial theater. Her work on “The Lion King” remains a touchstone, especially for anyone interested in immersive visuals.

She refused to hide the mechanics. Masks do not conceal the actors; they extend them. Puppets are visible; the operators’ bodies are part of the composition. Fabrics, rods, and hinges are not shameful technology to be disguised. They are beautiful in their own right.

Taymor’s visual language respects the audience enough to let them see the trick and still feel the magic.

This approach matters for immersive and site-based artists. When you are up close with the audience, you cannot rely on distant illusion. Embracing visible craft invites spectators into a co-creative mindset: they accept the world precisely because they see how delicately it is built.

Taymor’s other stage works, such as “Juan Darien” and “The Green Bird,” show a consistent interest in myth, ritual, and transformation. Her stage pictures often feel carved out of some shared dream vocabulary: masks that suggest both animal and ancestor, scaffolds that resemble bones, fabrics that carry wind and blood.

Her career has not been without controversy or misstep. That is useful to remember. Pushing visual form takes risk. Some projects strain budgets, safety, or coherence. For contemporary designers looking at her path, it is worth admiring the ambition while remaining honest about the costs and the need for clear collaboration and care for performers.

Designers who turned detail into storytelling

A single lamp on a desk, scratched and slightly crooked, can tell you more about a character than a full page of exposition. The best designers know this deeply and quietly.

Costume and scenic design as character x-ray

In the 20th century, women increasingly lead costume departments for major houses. Names like Tanya Moiseiwitsch and Motley (the collective that included women such as Sophie Harris) intersect costume and set design, shaping entire visual worlds.

Catherine Martin, although most famous for her film work with director Baz Luhrmann, approaches projects with a theater maker’s instinct. Look at “Moulin Rouge!” on screen and then at its stage adaptation. There is an exaggerated attention to texture: sequins that read across a room, peeling posters, layered reds that feel both seductive and slightly decayed.

Her background in theater informs her sense of sightlines and scale. She designs not just for pretty pictures, but for how garments move under harsh angles of light and constant choreography. When sets transition, she considers the rhythm of that change as part of the score.

In strong design, surfaces are never neutral; they carry history, class, taste, and intention.

Tharon Musser, mentioned earlier, handled light with similar precision. A warm sidelight at ankle height can carve a chorus line into sculpture. A cold top light on a bare stage can turn a confession into interrogation. Her cues did more than “help the audience see.” They sharpened the psychological edges of moments.

For immersive theater makers, these design histories are not academic. They are practical lessons. If you are building a 360-degree room that the audience will walk through, every detail needs the same intentionality Musser gave to a single cue or Martin gave to a single bead.

Spatial thinking and immersive instincts

Many women in theater design have had to think spatially in resourceful ways, simply because their budgets were smaller and their authority more contested. That pressure, while unjust, sometimes produced brilliantly lean work.

Consider off-off-Broadway designers working in converted storefronts, churches, basements. They stretched fabrics instead of building walls. They used light and sound to imply distance. They borrowed everyday objects and let context turn them uncanny.

This thrift is not the goal. Better funding and equitable respect are necessary. Still, there is a specific kind of creativity that emerges when women designers are forced to argue for every square meter of platform, every extra dimmer. They learn to justify choices with clear narrative reasoning:

– What story does this staircase tell that a ladder cannot?

– How does the distance between these two doors map to the emotional distance between characters?

– Why should this room feel three degrees colder than the hallway outside?

Those are the kinds of questions that make immersive space feel purposeful rather than gimmicky.

When women control the visual grammar of a room, the audience often feels less like a customer and more like a guest invited into a lived world.

What contemporary makers can learn from these histories

If you create or design theater now, especially immersive work, this history is not a museum. It is a toolbox.

First: authorship. Aphra Behn shows that you can write boldly under pressure and still keep your humor intact. Modern playwrights facing commercial demands can look to her for courage: the need to sell tickets does not forbid complexity or sharpness.

Second: presence. Siddons and Bernhardt embody an almost architectural sense of how a human body fills space. For any performer or director, studying them is not about copying their style but about learning how to balance stillness and explosion, how to make a single turn of the head land like a scene change.

Third: visible craft. Loie Fuller and Julie Taymor share an instinct to foreground mechanism. In immersive settings, audiences are closer, more alert to artifice. Hiding the wires often takes more energy than it gives back. Letting people see puppeteers, projection rigs, or costume changes can actually deepen engagement, as long as those elements are composed thoughtfully.

Fourth: structural thinking. Hallie Flanagan and Cheryl Crawford worked on the systems side. Artists today, especially women, often still have to invent the containers that will hold their work. That might mean forming collectives, building popup venues, or negotiating with civic bodies. Their example shows that making space for risk is itself a creative act.

Fifth: language as space. Hansberry, Fornes, Parks, Churchill, Kane each treat text as a spatial score. Immersive creators can treat dialogue and monologue not only as sound, but as pathways. Where is this line spoken? Into whose ear? Standing, sitting, in a stairwell, through a door? Those choices echo the playwrights’ own sensitivity to where words land.

Good immersive work does not simply surround people; it invites them into the same precision of attention that these women practiced on page, stage, and in the studio.

There is also a warning embedded in this history. Many of these women were isolated in their time, treated as exceptions instead of part of a broad, shared movement. That isolation can be exhausting. Contemporary theater makers have the chance to correct this by building lineages openly: acknowledging teachers, influences, collaborators, and the many women whose names never made it onto posters.

For anyone working in set design or immersive theater, studying these figures is not about nostalgia. It is about seeing how questions you face now have been asked, in other forms, across centuries:

– How do you make an audience care?

– How do you use a limited space to suggest an unlimited world?

– How do you keep control over your work when others want to turn you into mere decoration?

Women in theater history have answered those questions with stubborn clarity. Their answers live not just in biographies, but in the textures of sets, the angles of light, the rhythms of cues, and the stubborn decision to step into the light again, and again, and again.