The plywood floor flexes softly under your feet. A grid of hidden seams catches the spill of a single work light, turning the stage into a quiet puzzle. Platforms slide, walls pivot, a stair that was a throne ten minutes ago is now the back step of a dingy nightclub. Nothing is fixed. Everything is waiting for its next role.

Modular stages are exactly that: a puzzle you can keep solving, night after night, city after city. They are built from repeatable units that lock together, travel well, and still have the grace to disappear behind the story. When they are designed with care, they let you shift from cabaret to courtroom with a few moves, fit into a historic hall one week and a shallow black box the next, and survive the truck, the road, and the impatient get-in. The magic is not in the trick pieces. The magic is in the logic behind them.

What “modular” really means on a stage

Modular is not just a stack of standard platforms. It is a way of thinking about the show as a system.

At its simplest, you are working with repeatable parts that can be combined and recombined:

- Structural units (decks, legs, frames, truss, towers, stairs)

- Surface units (floors, facings, railings, claddings, soft goods)

- Connection methods (clamps, bolts, coffin locks, pins, magnets)

Each has a job. Each has limits. Each must speak the same “language” so that the system remains stable and predictable.

Modular design is less about clever pieces and more about clear rules that everyone on the team can understand at 3 a.m. in a loading dock.

If every show is a new alphabet, nothing travels well. If every show is the same alphabet, every sentence starts to sound the same. The art is in deciding what is fixed and what stays fluid.

Designing for flexibility: space, story, and time

Start with the rooms, not the drawings

Before drawing shapes, you need to know what kinds of rooms this stage will live in. Not in vague terms. Precisely. Measure them if you can. If you cannot, work with honest ranges.

Use a simple table like this when you start:

| Venue type | Stage width (min/max) | Stage depth (min/max) | Grid height (min/max) | Access / load-in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historic proscenium | 8m / 12m | 6m / 9m | 7m / 12m | Dock + ramp, narrow doors |

| Black box | 6m / 10m | 5m / 8m | 4m / 7m | Street level, no dock |

| Found / immersive site | Varies | Varies | Low / unknown | Stairs, uneven floors |

The ranges are your real “proscenium.” They tell you how deep a unit can be before it stops fitting, how high a tower can go before it hits a sprinkler, and how wide a wagon can be before it cannot turn a corner in a corridor.

Design choices that feel bold in a drawing can become reckless in a village arts center with a low grid. A modular stage that travels well respects the worst venue in the tour, not the best.

If your tallest scenic tower only just clears your home grid, it is not modular. It is a trap waiting for its first low ceiling.

Scenes as spatial states, not pictures

Flexibility does not begin with shapes. It begins with states.

Instead of designing a separate set for each scene, think in “modes”: arrangements of your modules that support very different behaviors in the same space.

For example, if you are designing an immersive piece that includes:

– a courtroom

– a cabaret

– a barracks

– a corridor for one-on-one scenes

You might not need four different worlds. You might need:

– an “assembly” mode with clear sightlines, consistent focus, and a defined front

– an “intimate” mode with carved corners, low ceilings, and visual privacy

– a “spectacle” mode with height, distance, and open air

– a “transition” mode that gives people a sense of movement and reorientation

You then ask: How can a limited family of units produce these four modes? Where do the walls swing, what rises, what hides? You are sketching not just pictures, but the transitions between them.

The real test of a modular stage is not how many looks it can make, but how gracefully it glides from one state to another under pressure of time and human bodies.

Structural logic: grids, modules, and the art of the constraint

Choose your grid like a composer chooses a key

Your module grid is your key signature. 4×4 feet. 2×1 meters. 1200 mm. Whatever it is, commit to it early and stick to it.

This choice affects everything:

– How platforms join

– How walls line up with floor seams

– How wagon tracks can repeat

– How lighting positions and masking can stay clean

A strong grid protects you from chaos later. You can still have irregular shapes, of course. You can slice diagonals, curves, and voids. You just anchor them to a structure that your crew knows by heart.

If your crew can guess a dimension just by looking at the tape marks, you are probably working with a grid that is doing its job.

Avoid the temptation to tailor each show to a slightly different module system. That is design self-indulgence at the expense of everyone who has to build, store, and tour your work.

Platform families and their hidden personalities

Modular decks are more than rectangles with legs. Each dimension has a character on stage.

– Long, shallow platforms (say 2×8 feet) feel like catwalks, docks, or thresholds.

– Squarish platforms (4×4 feet) feel solid, monumental, like blocks or islands.

– Slender steps and landings carry rhythm. They invite pacing, small shifts, hesitations.

The more you learn these personalities, the more you can design scenes that move through them like choreography, without needing a new unit for each story beat.

Build a “core family” of platform sizes that you will reuse across productions. For instance:

| Unit | Size | Common uses |

|---|---|---|

| Deck A | 2m x 1m | Risers, shallow thrusts, running pathways |

| Deck B | 2m x 2m | Islands, acting platforms, main level changes |

| Deck C | 1m x 1m | Steps, corners, fills, asymmetry details |

You can articulate level changes, balconies, runways, and pits with only these three units and a clear rule for legging and bracing.

Weight, height, and the sin of ignoring physics

Modular design that ignores loading is cosmetic, not serious. Theatrical weight is real weight. Touring adds fatigue.

Think in terms of:

– Load per unit: How many people can stand on a deck? What about rolling heavy set pieces or instruments?

– Point loads: Will someone jump, land, or drop a prop in one corner every show?

– Lateral forces: What happens when performers lean on that pivoting wall night after night?

If your units are overspecified, you might pay dearly in transport weight and handling. If they are underspecified, you will pay in repairs, fear, and potential injury.

Every “flexible” piece has a breaking point. Your job is to place that far beyond what any performer or crew member will ever ask from it.

Connections that travel: hardware, habits, and speed

Fasteners as choreography

Connections are not just technical details. They shape the rhythm of your fit-up and changeovers.

A platform that bolts together with eight different types of fixings will slow your day and increase errors. A platform that locks with two reliable connection types, in predictable positions, turns set-up into a muscle memory sequence.

Common connection languages for modular stages:

– Coffin locks for platform edges

– Spigots or pinned sockets for quick post insertion

– Standard scaffold couplers for rails and ladders

– Toggle clamps or rated magnets for light removable facings

Pick your language and limit the dialects. The more repeated the method, the easier it is to train new crew in new venues.

Color, code, and the kindness of clarity

Touring is tiring. People read less when they are tired. Label your pieces as if everyone handling them has never seen this show before.

Think beyond a scribbled number in marker. Use:

– Color-coded ends or legs for different heights

– Engraved or routed labels that survive repainting

– Simple pictograms for rotation or “this side up”

Create reference diagrams that match the labels exactly, with no artistic flourish. These diagrams are not for the audience. They are for the crew who must read them under work lights, on the floor, with gloves on.

Good labeling feels like respect for the people who move your ideas from truck to stage and back again.

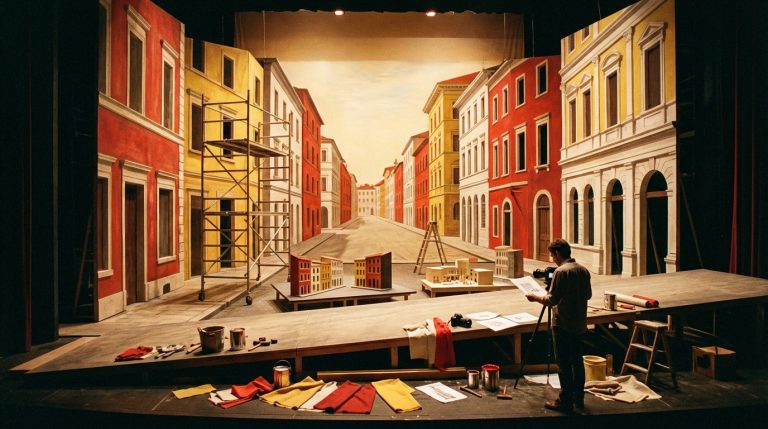

Surface, finish, and the illusion of permanence

The skin that hides the machine

Modular stages can look temporary, like exhibition halls. That is the cliché you should fight.

You can keep a powerful, repeatable skeleton of steel, ply, and truss hidden behind a very specific skin that changes from show to show.

Think in layers:

– Structural layer: the frames and decks you keep.

– Interface layer: bolt rails, t-nuts, battening points.

– Surface layer: claddings, trims, flooring, scenic detail.

By separating these, you can re-skin a familiar structure so that it feels bespoke, not generic.

For immersive work, this matters even more. Audiences are close. They touch surfaces. They notice repeated patterns, screw heads, unpainted brackets.

Finish for touch, not just sight

On a modular stage that travels, finishes suffer. Corners chip, handrails scuff, floors wear under shoes and wheels.

Design finishes that can age gracefully:

– Slightly textured paints that can take a quick roller pass before each run.

– Sacrificial edge trims that can be replaced without rebuilding.

– Removable floor vinyl or hardboard sheets that can be flipped or swapped.

Texture choices also shape the experience. A bare plywood edge with a visible grain tells a different story from a slick, sealed fascia. Neither is inherently better. The wrong one for the story, though, will fight you every night.

If the world is meant to feel improvised, let some of the modular seams show. If it is meant to feel absolute, disappear them ruthlessly.

Designing for travel: trucks, cases, and the tyranny of volume

Flat is good, but nesting is better

Travel is not only a test of durability. It is a test of volume. A stage that needs two trucks instead of one is a very expensive mood.

Flat units are easy to love, but if every platform has fixed legs and bracing, your truck pack will grow fast. On the other hand, fully knock-down units can become a forest of loose parts.

The trick is in how pieces nest:

– Platforms with telescoping or removable legs that pack under or within the deck.

– Walls that hinge in half or into thirds, with protected finished surfaces.

– Stair units that tuck into each other like Russian dolls.

Plan your pack in the design phase, not as an afterthought. Draw real truck footprints with realistic internal dimensions. See how your modules puzzle together. Often this exercise reveals which dimensions are helpful and which just waste air.

Road cases vs raw stacking

Not every show can afford custom cases for every unit. Yet throwing painted flats and platforms into a truck with only ratchet straps is not a neutral choice; it is a choice for damage and repainting.

Consider a hybrid approach:

– Cases or crate frames for fragile or high-value items (fine finishes, complex mechanisms, lighting).

– Raw stacking with edge protectors and blankets for heavy-duty platforms and frames.

– Dedicated “spacer” pieces whose only job is to protect others during the pack.

Label the pack order. Photograph it once you find an efficient arrangement. Use those photos as part of your touring bible.

An elegant pack is part of the design. It is the reverse choreography of the striking process, drawn in negative space and ratchet straps.

Speed of change: rep scenes, festivals, and shared venues

Changeover windows as design constraints

If your show is touring into houses with rep seasons, the stage will not belong to you for long. You might have two hours to build a world and thirty minutes to vanish it.

Design with these windows in mind from the beginning:

– Avoid huge, single-purpose units that require many hands.

– Favor subassemblies that can come in whole, be pinned in place, and wired quickly.

– Pre-rig as much as you safely can in the wings, on dollies or wagons.

For modular stages in festivals or shared immersive spaces, design states that can “hibernate” without complete removal. A balcony that slides into a wall, hiding its presence. A bar that folds into a flat counter, serving another show.

Silent changeovers for immersive work

For immersive and close-up performances, changes may happen with the audience present. There is a special pressure here. The theater cannot sound like a construction site.

Solutions are often simple, but they must be deliberate:

– Use nylon or rubber on rolling units to reduce noise.

– Avoid bare metal-on-metal contact where you can insert plastic or timber.

– Design one hand per action where possible, so crew can work quietly and confidently in the dark.

The goal is to let the space breathe between scenes without breaking character. The modular pieces move, but they should feel like the room is exhaling, not being rebuilt.

Performers, audiences, and the human scale

Modularity that respects bodies

A platform is not just a number on a plan. It is an ankle waiting to twist, a leap waiting to land, a skirt waiting to catch.

For a modular stage:

– Standardize step rises and tread depths. If your steps shift between venues, keep the ratios constant so muscle memory remains valid.

– Mark edges and height changes where sightlines are poor, using subtle paint shifts or trims that work scenically.

– Give performers enough real rehearsal time with the modular configurations they will meet on tour, not only with a fixed rehearsal stage.

Change the shape, if you must. Do not change the logic of heights and distances without warning performers. Bodies remember relationships.

Audience proximity and modular honesty

In immersive or promenade work, audiences stand close to the mechanics. They see under platforms, behind façades, into the gap between a wall and the ceiling.

You must decide how honest to be. Either:

– Conceal aggressively, boxing in voids, masking frames, painting every shadow.

or

– Design the exposed structure as an intentional aesthetic: visible bolts, raw ply, theatrical hardware as part of the visual vocabulary.

What often fails is the middle path: an almost-real room with accidental glimpses of battening and cheap hinges that were never meant to be seen.

Once an audience can touch the set, it is not scenery anymore; it is architecture. Your modular joints become doors, columns, and lintels in their world.

Common traps in modular stage design

Trying to do everything with one system

A single stage system cannot solve every project. If you try to stretch one modular kit across wildly different productions without reconsidering its logic, you risk visual fatigue and clumsy compromises.

It is healthy to have more than one “family” of modular language in your practice:

– A compact steel-and-ply system suited to touring drama and tight venues.

– A rugged, taller system suited to open venues and spectacle.

– A lighter, reconfigurable system aimed at immersive or site-responsive work.

Reusing is wise. Forcing reuse where it does not fit is not.

Overcomplicating mechanisms

Designers often fall in love with clever devices: hinge systems, telescoping bits, sliding secrets. On the road, every fancy joint is a future failure.

If a mechanism can be replaced by a simpler manual movement with choreography and light, it often should be. Keep mechanisms for what humans cannot do safely or at all: heavy lifting, high travel, very fast or perfectly repeatable motion.

The rest can live in blocking and crew practice.

Ignoring maintenance in the concept phase

Modular stages see more cycles of assembly and disassembly than fixed sets. Every cycle loosens fasteners, wears holes, and chips paint.

Plan from day one:

– Clear maintenance points: where bolts should be checked, where lubrication is needed, where paint will chip.

– Access: never bury a critical bolt behind fixed cladding.

– Spare parts: extra legs, bolts, locking mechanisms traveling with the show.

These choices rarely appear in mood boards. They matter a great deal after the tenth venue.

Modular stages for immersive and site-responsive work

Working with irregular rooms

Immersive shows often occupy rooms that were not built for performance: warehouses, basements, galleries, underused offices. The walls are not square. The floors may slope. Columns appear exactly where you do not want them.

Modular staging helps here if you think of your units as “negotiators” between the fixed architecture and the dramaturgy.

You can:

– Build consistent level changes that sit over uneven floors, giving performers safe, known surfaces.

– Wrap awkward columns with modular facades or balconies, turning them into characterful elements.

– Create “bridges” between rooms that feel deliberate, instead of corridors of exposed cabling and black drape.

The key is respect for the host space. Your modular system should touch lightly, fix where needed with minimal intrusion, and leave the building much as you found it.

Audience flows and reconfigurable routes

In immersive shows, the same modular wall can be a corridor boundary one night and an entrance portal the next, depending on the route design.

Plan your units so that:

– Doors can swing both directions, or panels can slide aside to open wider flows.

– Sections can be reversed, flipping “backstage” and “onstage” sides for different track designs.

– Sightline management (through slits, windows, lattice) can be adjusted without rebuilding.

This flexibility lets you evolve the show over time, trying new audience paths or handling different crowd sizes, while still moving the same base kit from venue to venue.

In immersive design, modularity is not just structural; it is dramaturgical. You are building a story machine that can be rewired between runs.

Working with budgets, crews, and reality

Budget as a sharp-edged design tool

A modular stage that travels is rarely cheap at the beginning. It can pay off across seasons, but that promise is only real if you treat the initial build as an investment in a long-term practice, not a one-off.

This has consequences:

– It may be wiser to simplify the look of the first show to afford better structure and hardware that will survive future use.

– Custom sculptural units that cannot be reused should be chosen carefully, with clear artistic justification.

– Cheap hardware and softwood legs may look thrifty, but they rarely survive touring and reconfiguration.

If your producers expect modularity to “save money” immediately, push back. Explain where savings appear: reduced build time for future shows, fewer new units, smoother packs, less overtime in rep houses.

Training crews as part of the design

Modular systems rely on people knowing how to handle them. The design is incomplete until the handling is passed on.

Include in your package:

– Simple assembly manuals with photos, not just CAD drawings.

– Clear notes about what must never be done (for example, standing a wall on its thin edge).

– A short, repeatable training session for new crew during early venues.

The more your system spreads across seasons and teams, the more you are designing a culture of use, not just objects.

When modular is the wrong choice

Sometimes, a story wants a set that cannot move. Or a venue schedule gives you so much time to build in place that modularity would add complexity without gain.

It is healthy to say no to modular design when:

– The show will never travel or remount, and storage is not possible.

– The space has such unique constraints that any generic skeleton would fall short.

– The scenic language relies on continuous, organic forms that would be weakened by regular seams.

In such cases, a one-off build tailored tightly to the architecture can carry more poetry and less compromise. A good designer knows when repeatability would flatten the experience.

Pulling it together: a way of working, not a fashion

Modular stages are not a style trend. They are a way of thinking about responsibility: to venues, to crews, to budgets, and to the material itself.

You listen to the rooms the show will visit. You choose a clear structural grammar and stick to it. You design for the tempo of changeovers, the weight of trucks, the patience of technicians, the ankles of performers, and the fingertips of an audience leaning against a railing that has to feel safe.

If you get it right, the audience never thinks about any of this. They feel a world that adapts and breathes and seems to belong naturally in each place it appears. Behind that ease lies a quiet grid of units, joints, packs, and practiced hands: a stage that is ready to travel, ready to shift, ready to become what the story needs next.