The glass is almost invisible. A pane, tilted at an angle, catching light that should not be there. Behind it, a hidden room glows. A figure appears where there was only empty space a moment before, hazy and luminous, as if memory had learned how to walk. The audience leans forward. No code. No render farm. Just light, reflection, and nerve.

That is the heart of special effects: making the impossible feel close enough to touch, using whatever tools the age can offer.

The short answer: special effects have shifted from clever tricks with glass, smoke, and painted flats to dense layers of digital imagery and physics-based simulations. But the spine has stayed the same. Every era takes the same question, “How do we make this feel real enough?,” and answers it with its own materials. Pepper’s Ghost used reflection and careful lighting. Early cinema used double exposure and miniatures. Optical printers and motion control brought precision. Today, CGI builds worlds out of polygons and pixels. The craft did not vanish; it migrated into code, compositing, and simulation. The artistry lives in the choices: when to stay tactile, when to go digital, and how to make both speak the same visual language.

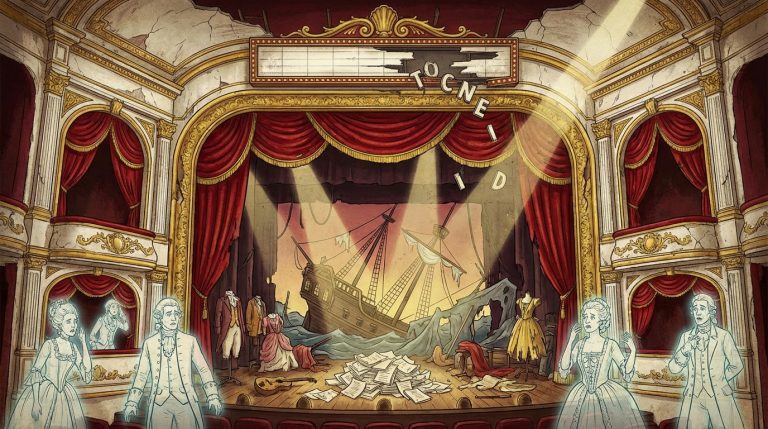

The ghost in the glass: Pepper’s Ghost and the birth of illusion

Before pixels, before film, before audiences shrugged at dragons on streaming platforms, there was a stage, some gas lamps, and a sheet of glass.

Pepper’s Ghost is, at its core, a reflection trick. But in practice, it feels like stage alchemy.

Picture a Victorian theater. The auditorium smells faintly of dust and warm oil. Footlights wash the stage in a soft amber glow. The audience sees an empty room set: a parlor, a crypt, a haunted study. Hidden below the stage, at a right angle to the set, sits another room, brightly lit, where an actor waits in the dark.

Between audience and stage, a large sheet of glass sits at an angle, almost invisible. When the hidden actor’s room is lit, their reflection appears on the glass, hovering inside the “empty” set. The actor moves, the ghost moves. The light fades, the spirit melts away.

Pepper’s Ghost taught an early, permanent lesson: an effect is not about technology; it is about controlling what the audience thinks they are seeing.

For set designers and immersive artists, Pepper’s Ghost is still a quiet workhorse. It lives in haunted houses, theme parks, shop windows, and experimental installations. It is cheap, fragile, and deeply physical. It demands precision:

| Element | Effect on Illusion |

|---|---|

| Glass angle | Controls alignment of the ghost with the physical set |

| Lighting ratio | Determines how solid or translucent the ghost appears |

| Background brightness | Too bright, and the reflection melts into glare |

| Viewer position | Shifts perspective; can reveal the trick if poorly planned |

The glass teaches humility. Every reflection has a source. Every ghost has a light cue. That same awareness carries forward into film and CGI: where is the light coming from, and what does that imply?

From stage trick to celluloid magic: early film effects

When cameras arrived, stage illusion stepped into a box of flickering shadows. The frame became the proscenium. The lens became the pane of glass.

Early filmmakers treated film like a magic toy. They stopped the camera, moved objects, started it again. People vanished, heads rolled off shoulders, cars teleported. It was crude and delightful. But very quickly, special effects became less about surprise and more about building worlds.

Once you had a strip of film, you could cut it, re-expose it, overlay it. Film was not just a record; it was a surface that could be painted with light more than once.

Where Pepper’s Ghost split reality into seen and hidden, early cinema split time itself, stitching moments together so that cause and effect felt continuous, even when they were not.

Key techniques began to form a vocabulary:

- Double exposure: Running the same film through the camera twice to layer two images, creating ghosts, clones, or visions.

- Matte painting: Blocking part of the frame during filming, then rewinding the film to expose the blocked area later with a painting or another shot.

- Miniatures: Building small-scale models of ships, cities, or landscapes and photographing them to appear full size.

- Optical printing: Using a machine that re-photographs film frames to combine multiple passes into a single composite shot.

For a set designer, matte paintings were spiritual cousins of backdrops. The difference: they sat inside the camera, not behind the actors. A cliff face on a painted matte had to match a physical ledge built on the stage. Horizon lines, light direction, color temperature: any mismatch would break the illusion.

The optical printer functioned as an invisible stage manager, aligning layers with almost mechanical patience. A spaceship, a star field, a cloud of smoke, all on separate strips of film, brought into a single frame. It looked effortless on screen. Behind the scenes, every mistake meant starting again.

Spaceships, monsters, and the age of miniatures

By the time science fiction and adventure films grew ambitious, miniatures had become an art form of their own.

Imagine a star destroyer model, several meters long, floating on a black stage. Every surface detailed with kit-bashed plastic: tank parts, ship hulls, vents, pipes. The camera creeps past it, its motion carefully controlled, repeating the same path over and over so lights, explosions, and passes can be layered later.

This is not just model making. It is architectural thinking. Every panel line is a design decision. Every scorch mark tells a story: where did this ship fight, what did it survive?

Lighting miniatures demanded care. A small model lit with normal film lights betrays its scale. Shadows fall too sharply, reflections feel wrong. So cinematographers used softer light, longer lenses, smoke in the air. They treated the model as if it were enormous.

Miniatures worked because artists respected scale. They did not cheat the physics; they coaxed the viewer’s eye into believing the mass.

For stage and immersive work, miniatures share a thread with maquettes and previsualization. You might build a small model of a set to test sightlines. Film pushed that model straight into the final image.

The analog threshold: motion control and optical precision

As audiences grew more visually literate, simple tricks lost power. You could no longer hide a sloppy matte line in grain and darkness. Effects had to withstand close scrutiny. The answer was repeatable motion and optical control.

Motion control rigs allowed cameras to repeat the exact same move again and again. That meant different elements of a shot could be filmed separately and combined later without misalignment. One pass for the ship, another for its running lights, another for explosions, another for star fields.

The process was slow and unforgiving, but it allowed a dance between physical and photographic elements that felt seamless to the viewer.

On the optical printer, compositors layered these elements carefully. Every exposure choice was a commitment. Too much brightness, and the image blew out. Too little, and the elements felt pasted on. There was no “undo” button. Only more film, more time, more care.

This analog discipline shaped an attitude that still matters in the digital age: do not fix everything in post. Design the shot at the beginning. Know where the camera lives, where the light comes from, what the foreground and background are supposed to communicate.

For set designers, this mindset resonates. If the camera is posted too high, a beautifully aged floor is wasted. If the actor never crosses that doorway, the detailed frame remains unseen. Every choice must serve the audience’s eye.

The leap into pixels: early CGI as an extension of practical craft

CGI did not arrive fully formed as world-swallowing digital spectacle. At first, it was strange, limited, and a little fragile. Wireframe models, chrome spheres, flat-shaded shapes. It looked like sculpture trapped inside a computer.

What changed everything was not only computing power, but the meeting of traditional craft and new tools. Model makers, animators, photographers, and coders sat together and argued about shadows.

Early CGI could not match the richness of light that practical sets and miniatures offered. What it could do, even at the start, was move objects in ways that cameras and rigs could not. Morphing faces. Smooth camera moves around impossible structures. Flocks of objects obeying mathematical rules.

CGI became powerful when it stopped trying to be a cheap replacement for physical work and started behaving like another material in the same toolbox.

Artists learned to integrate it with live action using the same principles that made Pepper’s Ghost and matte paintings work:

– Make the lighting feel motivated by visible sources.

– Match perspective; do not cheat vanishing points out of laziness.

– Use atmospheric perspective: distance should soften contrast and color.

– Marry the texture of CGI elements to practical surroundings.

A digital dinosaur looks wrong if it does not kick up dust that behaves like real dust. A digital window feels fake if it reflects nothing from the room in front of it. That awareness comes from years of working with glass, smoke, paint, and fabric.

Compositing: the invisible glue

As CGI grew in complexity, compositing emerged as the quiet center of modern effects. In the optical era, compositing happened in the printer. Now it lives on digital timelines, in layers and nodes.

Compositors sit with plates from live-action shoots, passes from 3D rendering, and elements from effects simulations. They balance them like a painter balancing foreground, midground, and background.

Color grading, grain matching, lens distortion, chromatic aberration: these subtle touches help separate polished digital creations from images that feel like stickers.

For an immersive designer, compositing feels very close to the layering of a physical installation. A scrim, a back projection, moving lights, practical objects: the audience only receives one blend of all of these. The artist thinks in layers; the viewer experiences a whole.

The digital flood: CGI everywhere, and the risk of weightlessness

Once CGI became cheaper and faster, it spread into almost every genre. Not just monsters and spaceships, but city extensions, crowd duplication, day-for-night, small fixes, and set cleanups.

Skies replaced. Wires erased. Rooftops extended. Entire streets fabricated to match two practical doorways.

On one hand, this expansion opened enormous creative range. Camera moves that would have been physically impossible became routine. Worlds that could never be built as physical sets could be explored with freedom.

On the other hand, something subtle began to slip out of some productions: weight.

A creature without real contact points with its set feels floaty. A city without enough midground detail feels like a backdrop, not a place. Overreliance on clean, perfectly controlled CGI can drain an image of texture.

The danger of modern effects is not that they are digital; it is that they can be too perfect, too smooth, too unconcerned with the mess of the physical world.

Mud flicks. Scratches accumulate. Materials fail in interesting ways. That is what makes sets compelling. When effects ignore that, images become forgettable.

Here is where set designers and practical artists hold an important line. They remind productions that audiences read surfaces. A corridor with real condensation on the walls feels colder than any simulated sheen. A prop door that sticks slightly on its hinges says more about a world than ten lines of exposition.

Hybrid thinking: practical plus CGI

Some of the most convincing modern work uses a blended approach: build what the actors can touch, extend what you cannot physically afford, simulate what is truly impossible.

A few recurring patterns stand out:

| Practical Element | Digital Partner |

|---|---|

| Partial set (foreground walls, floor, key props) | Extended environment (distant buildings, sky, mountains) |

| Creature close-up head or limb | Full-body animation for wide shots and stunts |

| Real explosion, debris, dust on set | Additional scale, shockwaves, and repeated elements |

| Miniature for complex destruction | Digital enhancement to hide seams and add scale |

The creative question becomes: what does the actor need to feel? What does the camera need to see? Where can digital work blend into that tactile base without calling attention to itself?

As an artist in immersive theater or set design, this is directly relevant. Projection mapping on a textured wall feels more grounded than on flat white. A holographic illusion over a physical sculpture carries more presence than a bare projection into empty air.

Back to ghosts: projections, holograms, and immersive illusions

Strangely, as CGI advanced, some experiences circled back to Victorian concepts, but with new tools. Pepper’s Ghost had a resurgence in theme parks and live events, often paired with high-resolution projection and LED screens.

Instead of simple glass and one hidden room, there are angled screens, layered content, and motion graphics. The ghost might be a 3D-rendered character, composited live onto a reflective foil. The audience sees a phantom that reacts in real time.

The principle is the same: a hidden image, a reflective surface, a carefully controlled field of view.

For immersive designers, this is fertile ground. A performer can share a stage with their own projected “spirit,” delayed by a beat. A room can appear to grow deeper than its physical walls allow. Mirrors, scrims, and projection surfaces turn small spaces into visual corridors.

The oldest tricks are not obsolete; they are raw material. They gain new power when combined with digital content that respects light, angle, and human perception.

The crucial thing is to remember that the viewer’s eye is still analog. It likes parallax. It notices when reflections misbehave. It trusts surfaces that react to light.

If a projected ghost does not dim when the house lights come up, the illusion crumbles. If a holographic figure casts no shadow on the floor you just lit, the audience will sense the gap, even if they cannot explain it.

AR, VR, and the invisible set

With augmented reality and virtual reality, special effects escape the physical screen entirely. The set moves into headsets and handheld devices. Walls appear where there are none. Creatures walk across your table.

In VR, the set designer becomes both architect and cinematographer. The viewer can look anywhere, walk anywhere permitted by the system. There is no frame to hide bad corners. The world must hold up from every angle.

In AR, the world is your stage, but you do not control all of it. The color of a user’s carpet, the brightness of their room, the reflections on their windows: all of it affects how convincing your digital elements feel.

This creates a different kind of discipline:

– Use lighting models that adapt to real-world light as much as the device allows.

– Anchor digital objects to clear, physical landmarks.

– Accept that some environments will be hostile to your illusions and design fallbacks.

For immersive theater makers, AR offers strange, interesting possibilities: secret characters visible only through a device, ghostly overlays of past events in a room, interactive set extensions that appear when audiences look through a given lens.

But the old truths still apply. If your AR content ignores physical obstacles, or passes through solid furniture in clumsy ways, the spell breaks.

The craft under the spectacle: why design still matters

Across this entire evolution, from Pepper’s Ghost to CGI and beyond, one constant remains: the effectiveness of an effect depends on design choices made early and held consistently.

Technology shifts. Perception does not.

The human eye still reads:

– Light direction and softness.

– Scale through perspective and atmospheric haze.

– Material through texture, reflectivity, and wear.

– Emotion through framing and motion.

When an effect respects these, it feels plausible. When it ignores them, no render quality can save it.

This is where the sensibility of set designers, costume designers, and immersive artists remains crucial. CGI can fill a frame with complexity, but someone still has to decide:

– How lived-in is this space?

– What story do the walls tell?

– How much should the viewer see, and what should remain hinted?

An empty, spotless digital corridor can feel dead. Add a crooked sign, a smear of grime at hand height, a light that flickers just off rhythm, and the corridor begins to breathe as a place.

The best effects are not about showing everything; they are about choosing the right details to reveal, and trusting the viewer to complete the rest.

CGI, at its strongest, is like a vast paintbox. At its weakest, it tempts artists to fill every corner with noise just because they can.

Resisting the “more is more” trap

In many productions, the ease of adding elements digitally leads to visual overcrowding. More debris, more sparks, more creatures in the sky. More “wow.”

But audiences tire. The eye stops caring when everything screams at the same visual volume.

Practical effects posed a natural limit. Every extra explosion cost more money, more time, more risk. Each had to matter. Digital tools remove that friction. So designers and directors must impose their own restraint.

This is where physical reference helps. If you are simulating a flood in a set, go watch water poured through a model. Notice how it tends to cling to surfaces, where it pools, how it reflects. That observation may tell you that you only need one strong wave in the foreground, not five in the distance.

For immersive installations, less can also be sharper. One well-executed illusion placed in the audience’s direct path has more impact than a room full of half-convincing gimmicks.

From illusion to experience: what audiences really remember

Ask someone about a film or a piece of immersive theater they love, and they rarely describe the effect by name. They remember how it felt.

The cold of a corridor before a ghost appears. The sudden shift in light when a “solid” wall opens to reveal a hidden space. The way a city seemed to continue forever beyond the set, even if it was just a painting or a digital matte.

Pepper’s Ghost survives in the shared memory not because it is clever, but because, in a dark theater, the experience of seeing a ghost rise in front of you still triggers something primal.

CGI survives and expands because it can place us in views we could never have: flying above a collapsing building, drifting through the veins of a body, sitting on the shoulder of a giant.

But every one of these moments depends on respect for how we sense space, light, and presence.

For artists in set design and immersive theater, the evolution of special effects is not a story of replacement, from old to new. It is a stack:

– Reflection and glass.

– Paint and miniature.

– Film and optical printers.

– Motion control and analog precision.

– CGI and simulation.

– AR, VR, and responsive environments.

Every layer adds possibilities but also demands new discipline.

The future of special effects will not belong to the flashiest tools, but to the artists who can let digital and physical work together, quietly, in service of a single, clear experience.

Whether you are tilting a pane of glass in a black box theater or dialing in the subsurface scattering of a digital creature’s skin, the question is the same: what does the audience feel in that one, precise second when the illusion lands?

If the answer is vivid, if the environment and the effect speak the same visual language, the ghost in the glass is alive again, even when it is built from code instead of reflections.