Fog hangs low over the Willamette, swallowing the tops of the bridges. Headlights slide along wet pavement. Brick, steel, timber, glass. So much of Portland still feels like a stage set waiting for actors to arrive. Yet you can sense the absences too. Whole facades missing from the composition. Ghost outlines where buildings used to stand, like tape marks left on a rehearsal floor.

Portland keeps performing, but some of its best sets have been struck forever.

The short answer: Portland erased a remarkable collection of historic buildings that could have made the city feel richer, stranger, more cinematic. The ones we lost were not only architecturally beautiful, they were magnetic anchors for memory: ornate hotels that turned arrivals into theater, neon-drenched marquees that staged entire evenings, Chinatown landmarks that carried layered stories of migration and exclusion. For anyone designing immersive spaces, those lost structures are a lesson in atmosphere: how scale, material, light, and ornament can make a city feel like a living set, and how careless planning can flatten that texture in a generation.

This is a walk through some of Portland’s missing rooms. Not nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake, but an inventory of mood, geometry, and character we no longer have to work with. If you design experiences, you need to know what used to be on this stage.

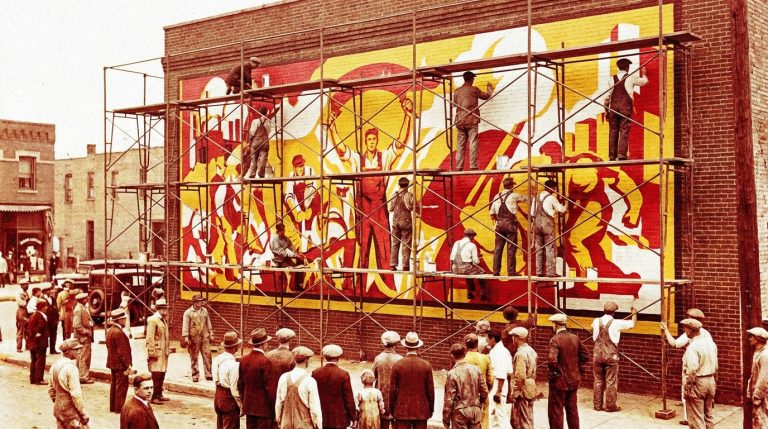

The City As Vanishing Set

Every city has demolition scars, but Portland’s are unusually theatrical. You can stand downtown, look around at grey glass and polite mid-rises, and feel that a more expressive version of the same street has been painted over.

Portland did not just lose square footage; it lost emotional scale, contrast, and the architectural “props” that give a place memory.

Historic buildings here were rarely subtle. They were intense: glazed brick in improbable hues, carved terra cotta piled like frosting, cornices you could see from blocks away. Many went down in short bursts of “urban renewal,” highway plans, and demands for parking. The result is a city where certain blocks feel a size too large for the stories they hold.

For set designers and immersive artists, this absence matters. Those vanished buildings once:

– Shaped how light moved through streets.

– Framed sightlines for approaching visitors.

– Dictated how people flowed, gathered, and lingered.

Now we work in a city where several key “anchors” have been removed. The interesting part is to treat those empty spaces as clues: what created such strong attachment that people still talk about them decades later?

The Portland Hotel: The Grand Lobby That Vanished

Step into Pioneer Courthouse Square and imagine it, not as a stepped brick plaza, but as a dense, ornate block filling nearly the entire site. Picture a steep roofline, dormers cutting into the sky, and a courtyard where the Square’s central space now drops away in brick terraces.

That was the Portland Hotel.

Completed in the late 19th century, it was once the kind of building that could overshadow the very courthouse that still stands next door. A rust-red, almost fortress-like pile, ringed with bay windows and crowned with a dense roofscape. It looked less like a hotel and more like a small city that had decided to curl up into a single block.

Inside, you entered another atmosphere entirely: Turkish carpets, carved wood, stained glass, oil paintings. Not subtle luxury, but theatrical opulence. Arriving there was an event. You did not just “check in”; you made an entrance.

The Portland Hotel turned arrival into ceremony. Without it, the city’s most central square feels strangely exposed, like a stage without a proscenium.

From a design perspective, the hotel did several things that the modern square cannot.

| Aspect | Portland Hotel | Pioneer Courthouse Square |

|---|---|---|

| Edge condition | Solid, vertical walls that held the street | Open, stepped edges that let space bleed outward |

| Height & mass | Tall, looming volume that defined a ceiling for the block | Low, mostly horizontal plane |

| Sensory tone | Enclosed, plush, shaded interiors | Exposed, public, hard-surfaced exterior |

| Experience | Ceremonial entrance and layered thresholds | Casual flow, minimal transition |

The plaza that replaced it has value. It gives Portland a civic living room. Yet the trade came with cost. The hotel created:

– A strong vertical frame for the courthouse.

– A series of intimate interior worlds.

– An unmistakable sense of “arriving in Portland.”

For immersive design, the lesson is sharp: grand hotels function like narrative devices. They compress the world into a lobby. They carry sound differently. They hold secrets in corridors and hidden parlors. Removing that container removes an entire type of story from the center of the city.

The Orpheum / Paramount Theatre: The Lost Proscenium

Imagine Broadway and Main when the light begins to drain from the sky. Modern traffic still hums, but picture one more thing: a tall marquee, blazing with bulbs, pouring warm light onto wet asphalt. A stream of people moves under it, tickets in hand, voices overlapping with streetcar bells.

That was the Orpheum Theatre, later renamed the Paramount.

The facade was ornate, in a careful, almost delicate way. Terracotta detail, tall arched windows, and a sign that claimed attention without shouting. Inside, a true movie palace: high plaster ceilings, intricate moldings, sweeping balcony. Films and live acts shared the same stage here. It was a room built to focus hundreds of pairs of eyes on a single frame.

The Orpheum held a simple power: it could capture an entire city’s attention in one room for two hours at a time.

It came down in the early 1970s, traded for standard office development. Portland has other historic theaters, but losing the Orpheum put a gap in the pattern. That corner lost its glow. The rhythm of nightlife in that stretch changed.

From a spatial and theatrical point of view, the Orpheum offered:

– A clear narrative arc: street to lobby, lobby to auditorium, curtain to credits.

– Public spectacle: queues, meetups on the sidewalk, neon as social signal.

– A shared cultural memory bank: if you saw something there, it lodged in place.

The building also participated in the city’s visual vocabulary. Those stacked vertical signs that once punctuated downtown made the streets read more like an urban proscenium. Demolishing the Orpheum dimmed that script.

For set designers, the missed opportunity is obvious: a restored Orpheum could have served as a permanent, historic container for experimental performance, immersive film, or hybrid digital-physical work. Instead, we must invent these stages elsewhere, often from scratch.

Old South Portland: A Neighborhood Erased for Concrete

Now move south from downtown, toward the sweeping arcs of the I-405 and I-5 interchange. Picture the roar of highway, the grid stretched and broken. Between the overpasses, fragments of a neighborhood survive, but most of it is asphalt, retaining walls, abutments.

Once, this area held narrow streets, small wooden houses, small synagogues, corner stores, and a dense pattern of life. Old South Portland was home to immigrant communities, particularly Jewish and Italian families. Front porches faced tight sidewalks. Laundry hung in yards. Street-level life unfolded at human height.

The buildings were not grand in the way of the Portland Hotel. They were humble. But the ensemble mattered.

Urban renewal did not just tear down structures; it erased a shared set, leaving actors dispersed across a larger, less legible stage.

From an experiential standpoint, the old neighborhood offered:

– Short blocks and close-set houses that shaped intimate sightlines.

– Mixed-use corners where commerce and domestic life overlapped.

– Religious and social buildings scaled to the community, not the car.

Highways cut through that fine grain. Wide lanes replaced narrow streets. Sound swelled. Human-scale facades and ornament gave way to massive concrete forms with little visual give.

For immersive theater, neighborhoods like Old South Portland are gold. They provide ready-made backdrops with layered texture. They let audiences wander through believable domestic spaces, narrow alleys, and small community halls. You do not have to build much; the block does the heavy lifting.

Portland’s decision to punch freeways through this area removed one of its richest narrative fabrics. The few surviving structures and memorial markers feel like stage props left behind after the rest of the set has been carried away.

Portland’s Old Chinatown: The Vanished Gates

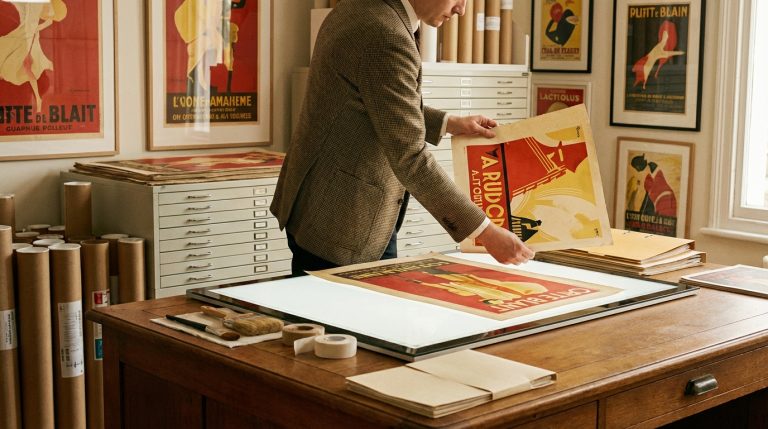

Walk today along NW 3rd and 4th, north of Burnside. You will find fragments: the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association building, the Hung Far Low sign (relocated), a few historic facades. But the original pattern of Portland’s Chinatown, centered slightly further south and west in the 19th and early 20th centuries, has been thinned, cut, rearranged.

The earliest Chinatown developed near SW 2nd and Stark, later shifting north. It held:

– Densely packed brick buildings.

– English and Chinese signage in layered bands.

– Lodging houses, club rooms, stores, and herbal pharmacies with deep, narrow interiors.

Visual clutter in the best sense: beams of painted wood, screen doors, hanging signs, light wells cutting through tight courtyards. Steam from kitchens mingled with street dust and candle smoke. It was not tidy, but it was visually dense and distinct.

Old Chinatown carried stories in every signboard and carved lintel; losing those layers flattens the narrative of who built Portland.

Much of this building stock was weakened by discriminatory policy, neglect, and deliberate clearance. Devaluation came first; bulldozers followed. The result is a district that still carries the name but lost much of its original physical depth.

For designers of immersive work, historic Chinatowns are complex. One must navigate stereotype, respect, and historical pain. Yet materially, those blocks offered:

– Repeating visual motifs: latticework, lanterns, bright color on muted brick.

– A compressed vertical scale perfect for intimate processions or hidden-door experiences.

– A tangible sense of crossing from one cultural environment into another.

In Portland, the fragmented remains demand careful reading. A fully intact Chinatown streetscape would present a rich, real-world “set” for stories about migration, exclusion laws, and community resilience. Without it, many of those stories risk drifting into abstraction, detached from the textures that gave them weight.

The Cornelius Hotel: Wrecked Ornament

On the corner of SW Park and Alder once stood the Cornelius Hotel, a slender, dignified building often called the “House of Welcome.” Where the Portland Hotel was heavy and almost fortress-like, the Cornelius was vertical and crisp, with white terra cotta ornament climbing its facade.

It was not tall by current standards: only a handful of stories. Yet its height, relative to the neighboring buildings, made it feel like a spine on the block. Tall, narrow windows. Decorative wreaths and swags. A strong cornice line that stitched the building into the surrounding air.

The interior was more restrained than the Portland Hotel, but still composed: patterned tile, wood trim, careful light fixtures. It opened in 1908 and served travelers for decades before fading and closing.

The Cornelius showed how much character can be held in a mid-size building; not monumental, but precise.

For many years, the facade sat vacant, its windows like blind eyes. Damage from fire and neglect mounted. In the 2010s, a partial rescue and redevelopment attempted to incorporate it, but much original detail had already been lost.

Architecturally, the Cornelius drew its strength from proportion and repetition. For people who care about immersive environments, buildings like that matter because they demonstrate how:

– Rhythm in window spacing sets an unconscious tempo for walking.

– Ornament at the pedestrian eye line creates intimacy.

– A clear vertical edge holds a street’s energy in place.

When we trade such facades for flat glass or blank concrete, we reduce the cues that help visitors establish emotional bearings. The loss is subtle, then accumulative. Block after block, the city becomes harder to “read” at a glance.

The Oregonian Building: A Tower of News

Before media went handheld, the news itself had an address. For Portland, that address once had a striking silhouette: the old Oregonian Building at SW 6th and Alder, erected in the late 19th century.

Picture a tall clock tower rising above a solid masonry base. Not as delicate as a European cathedral, but with some of the same vertical ambition. The building housed the newspaper’s offices and printing operations, and the tower extended the building’s influence into the skyline.

If you saw that clock, you knew where the news came from. The architecture turned information into presence.

The Oregonian Building converted abstraction into stone; “the paper” became a place you could point at.

By mid-20th century, the building was deemed outdated. It was demolished and replaced with a more generic structure that did not carry the same symbolic charge.

For city-making and for stagecraft, buildings like this matter because they:

– Personify institutions in legible, concrete form.

– Add vertical punctuation marks to the skyline.

– Provide natural gathering points in the city.

In immersive storytelling, giving your fictional worlds “addresses” lends credibility. In real cities, removing those iconic markers can make civic life feel less anchored. Without that tower, the concept of a “public square of ideas” becomes easier to overlook, because it no longer has a literal corner.

The Council Crest Amusement Park: An Elevated Fantasy

High above the city, Council Crest still offers some of the best views of Portland and its surrounding hills. Today it is a park with lawns, trees, paths, and the soft hum of conversation. But in the early 20th century, this hilltop was something else entirely: a small amusement park accessed by streetcar.

Conceptually, it almost feels too perfect: ride a trestle-hugging streetcar up through the trees, then arrive at a miniature fantasy of towers, rides, and pavilions. A carousel. A scenic railway. Structures edged with lights that must have glimmered like a crown above the darker hillsides at night.

Council Crest once served as Portland’s literal and symbolic “third act” location, a high vantage point where everyday life briefly shifted into play.

The park closed in the late 1920s. Most structures were removed. The site softened into the more naturalistic space we know today.

From an immersive design standpoint, the earlier version holds several compelling ideas:

– A choreographed approach: journey by transit as pre-show.

– Controlled contrast: dense urban core below, playful, elevated world above.

– Layered horizons: the city as shifting backdrop, not primary focus.

Losing the built part of Council Crest removed one of Portland’s purest examples of a purpose-built fantasy environment tied to public transit. Imagine designing seasonal, narrative-driven experiences that followed that same arc: streetcar to summit, performance against the lights below. The setting remains, but the architectural “sets” that once framed it are gone.

The Mark of Lost Houses and Corner Stores

It is easy to focus on marquee names: big hotels, big theaters, big towers. Yet a significant part of Portland’s erased fabric rests in smaller structures: Victorian houses on what is now the Lloyd District, corner groceries in Albina, rows of modest cottages in inner southeast.

Many vanished through piecemeal demolition. Fire here, parking lot there, an expanding commercial block a few streets away. Each loss felt small, rational, incremental. Together they produced swaths of the city that feel strangely scale-less.

Consider the ordinary late 19th and early 20th century Portland house:

– Wood siding, sometimes shingle, often painted in surprising combinations of blues, creams, greens.

– A steep front gable facing the street, reading almost like a stage flat.

– A front porch that held the threshold between private and public life.

Multiply that by dozens of blocks. You have a repeating rhythm of entrances, porch posts, stair rails. People on stoops. Kids on sidewalks. Shadows from small trees crossing horizontal siding.

Replace a handful of these with surface parking or anonymous boxes, and that rhythm stumbles. Do this across whole districts, and the script of how people use the street changes. Fewer eyes on the sidewalk. Fewer chances for sightlines that invite performance, chance encounter, or small, site-specific works.

In immersive arts, we often hunt for “authentic” spaces; the greatest loss in Portland may be the silent disappearance of thousands of such ready-made stages.

For artists today, this means more fabrication. More set builds to reconstruct what the city once gave for free. More careful scouting to find the leftover pockets where the older rhythm still survives.

What These Losses Teach Immersive Designers

Looking at a record of demolition can drift into numbness. Another facade down. Another parcel scraped. Yet for someone crafting experiences in Portland, the missing buildings sketch the boundaries of what we now must invent.

Several clear lessons stand out.

The buildings people miss most are not always the most “efficient.” They are the ones that framed emotion, ritual, and memory with clarity.

Atmosphere Beats Perfection

Few of the lost buildings were flawless. Some were awkward hybrids, out of date, or compromised by insensitive alterations. The Oregonian Building was heavy. The Portland Hotel could feel overbearing. Old South Portland’s housing was often cramped.

Yet atmosphere trumped perfection. Texture, light, and detail combined to shape distinct feelings tied to specific places. For immersive work, this echoes a familiar truth: audiences forgive flaws if the mood is strongly drawn. A chipped wall can feel more alive than a perfectly smooth one.

When designing new installations or temporary sets in Portland, think about:

– Strong silhouettes that will remain in memory once lights are off.

– Tactile surfaces that reward touch: carved wood, rough brick, patterned tile.

– Lighting treatments that exaggerate depth and ornament.

The city once had this sort of atmosphere built in. Now it must be carved back into neutral shells.

Thresholds Matter More Than Footprints

The Portland Hotel and the Orpheum did more than occupy ground. They choreographed entrance. Turning from the street into their lobbies or foyers felt like passing a mental curtain. Narrow doors leading to wide interiors; dark outer halls opening into bright rooms.

As we lose these types of thresholds, we end up with more flat transitions: sidewalk directly into open-plan lobby, parking lot into retail floor. Less ceremony. Less anticipatory space.

For anyone building immersive environments in the city now, the loss points toward a need to overdesign thresholds:

– Short transitional corridors.

– Shifts in ceiling height or floor materials.

– Gradual dimming or brightening of light as one passes inward.

Historic Portland once provided many such choreographed entry sequences. Their erasure leaves modern buildings feeling more exposed and abrupt.

Scale and Proportion Shape Memory

Look again at the set of vanished icons:

– Portland Hotel: a large body with intricate surface.

– Orpheum: mid-sized volume with a spectacular internal void.

– Cornelius: slender shaft of ornament.

– Oregonian: vertical marker offset from the main mass.

– Old South Portland: many small, repeated forms.

Each contributed a different type of scale to the streetscape. Large next to small, tall next to low. That contrast helps people build mental maps. It also sets up natural “stages” where a smaller building might become a focal point against larger neighbors.

As demolition removed older mid-rise and small-scale buildings to make space for wider roads, parking, or single large volumes, that nuanced layering flattened.

For design practice, this requires:

– Conscious introduction of varied scales inside single projects.

– Careful staging of “moments” where something small and detailed becomes the focus within a larger shell.

– Resistance to the temptation of uniform, continuous surfaces.

Historically, Portland’s varied structures provided that tension without being asked. Now it has to be intentional.

Working in the Gaps: Using Absence as Material

If you walk Portland with an eye for what is missing, you start to see patterns of absence as clearly as patterns of brick. The empty plaza where the Portland Hotel stood. The smooth office facades where the Orpheum sign once blinked. The wide hinge of highway where Old South Portland’s grid broke.

For an immersive designer, these are not only losses; they are prompts.

Every erased building is also a ready-made ghost story, a remembered set you can re-stage in unexpected ways.

Several approaches emerge:

Reconstructive Storytelling

Build experiences that temporarily restore or reimagine these lost structures, not as perfect replicas, but as felt presences. For example:

– A nighttime projection piece on Pioneer Courthouse Square, tracing the outline of the Portland Hotel and fading it in and out of the current brick steps.

– Audio walks where participants stand under an office tower while hearing layered soundscapes of an old news room in the Oregonian Building.

Here the design material is mostly intangible: light, sound, and guided attention.

Using Surviving Fragments as Portals

Portland still holds slivers of what used to be.

– A lone ornate doorway from a demolished facade, embedded in a newer wall.

– A small row of Old South Portland houses that escaped clearance.

– The last historic sign or window detail on an otherwise altered block.

These fragments can be activated as literal portals into other times. An immersive piece might:

– Stage performances that begin at such a fragment and then slip into adjacent modern interiors, playing on temporal tension.

– Install subtle environmental cues (sound, scent, small projected images) at these points, turning daily commutes into soft hauntings.

Designing New Work with Historic Sensibility

The aim is not fake nostalgia. It is to borrow the spatial intelligence of lost buildings.

From the Portland Hotel, we can copy:

– Deep, layered lobbies.

– Richly textured interior materials.

– Vertical segmentation of a facade to reduce apparent bulk.

From Old South Portland, we can adapt:

– Short sightlines that encourage turning, discovering, and reorienting.

– Porches and stoops used as intermediate audience zones.

– Tight squeezes between structures as moments of heightened intimacy.

From the Orpheum and Oregonian towers, we can echo:

– Highly legible landmarks that serve as meeting points.

– Strong signage and light cues that gather people without shouting.

Contemporary building codes and budgets set limits, but atmosphere and narrative order are largely design choices. Lost Portland provides a set of precedents, even if the bricks themselves are gone.

Why Memory of Buildings Still Matters

Some argue that cities must change. That buildings serve their time and give way to new forms. There is truth in that. Not every old structure can be saved, and not every glossy tower is devoid of character.

But when a city forgets its own spatial stories, it risks becoming thin. Designers then float experiences in abstract glass boxes, unmoored from the ground beneath. For an art form that relies on embodied presence, that detachment is dangerous.

Portland’s history of demolition offers a quiet warning:

If you erase too much of a city’s physical memory, you force every new story to start from zero, instead of weaving into a longer thread.

For those of us working in set design, immersive theater, and spatial storytelling, the remedy is not simply to mourn, but to:

– Study the proportions and moods of what has been lost.

– Let those patterns inform new spaces, temporary or permanent.

– Treat absences not as blank, but as charged sites with lingering lines of force.

Fog still rolls over the river. Headlights still streak through rain. Somewhere beneath the bricks of Pioneer Courthouse Square, the ghosts of bellhops and travelers still cross the lobby, heading toward rooms on upper floors that no longer exist. If we listen closely, we can hear the echo of those footsteps and build our next stages in thoughtful response.