The dust hangs in the air like old applause, soft and stubborn. Your footstep echoes against cracked terrazzo; a single work light throws a cone of pale yellow over torn velvet seats and a ceiling that once tried to imitate the heavens. Somewhere, behind the proscenium, a pulley creaks. The building is quiet, but it is not empty. It is watching you.

You stand in the aisle with one question: do you bring this theater back to what it was, or turn it into what it has never been?

The short answer: you should not pick restoration or modernization as if they are two enemy camps. The best renovated theaters feel like a truce between memory and function. Restore what carries character, story, and identity. Modernize what touches safety, accessibility, audience comfort, and production flexibility. When you let the original architecture be the lead actor and the modern systems be the crew in black backstage, you protect the building’s spirit while making it work for contemporary audiences, artists, and revenue.

Reading the building before you touch anything

The first decision is not paint, not seats, not sound system. It is point of view.

An old theater is not a blank slate. It is closer to a palimpsest, with every layer of renovation scraped and written over the last. An art deco ceiling under a 1970s acoustic tile grid. Marble hidden behind drywall. Stage machinery frozen in mid-century logic. If you treat it as a neutral container, you will flatten it. If you treat it as a fragile relic, you will suffocate it.

Before you choose restoration or modernization, decide what this particular theater is trying to be when it grows up.

Ask very blunt questions:

Who will use this place? Touring musicals, small experimental troupes, corporate events, film screenings, community dance recitals, weddings?

How many days per year do you need it active to survive?

What is the emotional promise to your audience? Grand night out in a historic jewel box, or adaptable black-box energy wrapped in a vintage shell?

Those choices decide the weight you give to authenticity versus flexibility.

Where the debate is real: restoration vs. modernization

Restoration asks: “What did it look like, feel like, work like in its prime?”

Modernization asks: “What does it need to be useful and sustainable now?”

Both questions are valid. Both are incomplete on their own.

Think of restoration as a close-up lens. It cares about original plaster profiles, historic paint schemes, period light fixtures. Modernization is a wide lens. It cares about HVAC distribution, acoustic isolation, rigging capacity, fire egress.

Trouble begins when one lens wipes out the other. Over-restoration can freeze a theater in amber, visually charming but technically frustrating, hard to program, hard to rent. Over-modernization can erase the very thing that drew you to the building: its personality.

The goal is not to keep everything old or make everything new. The goal is to let the building’s character do the talking while the new systems quietly do the work.

Key zones: what to restore, what to modernize

Your renovation choices live in different “zones” of experience. Some are highly visible, near the audience’s eye line. Some live in basements and behind walls. The wise move is to restore the surfaces that speak, modernize the bones that keep the place alive.

- Audience chamber and lobbies: restore as much distinct character as budgets and codes allow; hide modern systems in existing ornament and structure.

- Stage, grid, and backstage: prioritize modernization. Historic value is secondary to safety and technical capability here.

- Front-of-house facilities (toilets, bars, ticketing): modernize function, echo period detailing in materials and fixtures.

- Building systems (HVAC, electrical, fire, access): modernize decisively, then work backwards to mask or integrate visually.

This is not about compromise for its own sake. It is about each zone serving its role: story, safety, comfort, or income.

The audience chamber: the building’s face

The room where people sit and look toward the stage is the heart of restoration arguments. It is where the gold leaf lives, where murals peel, where chandeliers droop sullenly.

Here, restoration is powerful:

– Ornamental plaster: Repair, do not smooth away. Those moldings shape not just beauty, but acoustic reflection.

– Historic color: Older schemes were often richer and darker than the faded pastel you see. Research, then make a deliberate choice: faithful recreation or contemporary palette that respects original logic.

– Decorative fixtures: Retain or replicate key fixtures as visible jewelry, even if the guts hide LED retrofits.

But this is also where modernization must slip in, almost invisible:

– Integrated air supply and return concealed in balcony fascias, moldings, or seat platforms.

– Light positions planned with the architecture in mind, so you are not bolting crude black bars across historic plaster.

– Subtle acoustic treatment where needed, clad in period-appropriate fabric or millwork.

If the audience looks up and feels transported, you have done the restoration work. If they sit for two hours without sweating, freezing, or straining to hear, you have done the modernization work.

Lobbies and arrival: the first and last impression

The first 30 seconds inside the theater doors decide almost everything about perceived care.

Many older lobbies are either stunning but cramped, or brutally remodeled in some past decade. Your strategic choice:

– If the lobby has strong original bones (staircases, railings, stone floors, coffered ceilings), protect them. Clean, repair, recreate missing pieces. The lobby is where donors and photographers will fall in love.

– If the lobby is already mangled beyond clear heritage, give yourself more license. You can create a contemporary insert that respects the theater’s age without imitating it poorly.

The real modernization levers here are subtle:

– Lighting layers: Aim for warm ambient washes with focused highlights on architectural features. Avoid flat general light that erases detail.

– Clear sightlines: From the door, people should see box office, bar, wayfinding to toilets and auditorium without confusion.

– Acoustics: Control clang and echo with discreet soft surfaces, so pre-show crowds do not drown in their own noise.

Front-of-house is also where accessibility, quite literally, comes in the door. Level changes, ramps, accessible counters, lift locations all need uncluttered planning. The goal: nobody should feel like an afterthought.

Backstage: where nostalgia must step aside

Behind the proscenium, you are less in a museum and more in a workshop. Old fly systems, narrow wing spaces, rickety catwalks may hold sentimental appeal, but they can be dangerous and deeply limiting.

Here, modernization is rarely optional:

– Rigging: A modern counterweight or motorized system improves safety and increases programming flexibility. Historic hemp sets are rarely worth preserving beyond demonstration value.

– Stage floor: A resilient, flat, quiet floor matters more for performers than historic boarding that squeaks and snags casters.

– Power and data: Touring shows, film shoots, and event rentals need loading capacity, company switches, and reliable networking.

– Support spaces: Dressing rooms, green room, wardrobe, and storage may need radical reconfiguring to function.

Keep whatever historic backstage fabric you can, but do not let romance outrun safety or usefulness. The audience will never see your original rope locks. Performers will feel your new stage floor every night.

Light, sound, and sightlines: the invisible design battles

Sound and light are where historic charm can turn hostile.

Older theaters often have:

– Decorative domes that trap sound.

– Hard parallel walls that bounce slap echoes.

– Shallow balconies that block sightlines.

– Ornate chandeliers that block lighting positions.

You have to treat these as design challenges, not untouchable relics.

Acoustics: respecting the natural voice of the room

Many pre-amplification theaters were designed for the unamplified human voice. That is a plus for opera or acoustic drama. It can be chaos for amplified concerts.

Restoration-focused thinking might say: leave the room’s acoustics alone, they are historic. Modernization-focused thinking might cover everything with panels and absorbers until it sounds like a conference center.

The better path:

– Study the room: commission an acoustic survey. Understand reflection paths, decay times, problem frequencies.

– Work with the architecture: use fabric wall panels patterned to echo historic motifs, shaped ceiling clouds painted into existing coffers, discreet balcony fronts to break reflections.

– Plan for program types: you might need variable acoustics, such as deployable banners or curtains, to support both speech and music.

The audience should never consciously notice acoustic treatment. They should simply notice that they understood every word and felt every chord.

Lighting and sightlines: seeing without scarring

Where to put modern lighting in a historic envelope is one of the most delicate questions.

You want:

– Sufficient front light, side light, and specials to support serious productions.

– A rigging layout that does not make visiting designers curse.

You do not want:

– Visual clutter that pulls focus from architecture.

– A forest of truss that fights your plaster and murals.

This is where early collaboration between architect, theater consultant, lighting designer, and heritage advisor matters. Integrate lighting positions into balcony faces, organ lofts, or false vents. Design custom fixtures that echo period shapes while serving contemporary optics.

Sightlines are less poetic but just as critical. Old theaters love tall rakes and tight rows. Legroom and accessibility suffer, but so does view for modern staging that often pushes far upstage.

Sometimes seat count must go down to improve seat quality. That is a painful but often wise choice.

A smaller house with good sightlines and lighting is worth more, both artistically and commercially, than a larger house where a third of the audience peers around columns.

Systems you cannot see but will definitely feel

If the audience never talks about the HVAC, electrical, or fire systems, you have succeeded. But these lines on your plans may drive more of your budget than the gold leaf.

Here, you should lean toward modernization with conviction.

| System | Why it matters | Restoration angle | Modernization priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| HVAC | Comfort, air quality, noise | Reusing historic grilles, concealing ducts | Quiet operation, zoning, fresh air rates |

| Electrical | Safety, load capacity | Preserving historic fixtures as shells | New wiring, panels, emergency power |

| Fire & life safety | Code compliance, public trust | Subtle integration of devices | Sprinklers, alarms, egress, fire curtain or alternatives |

| Accessibility | Legal and ethical access | Respecting historic layouts where feasible | Ramps, lifts, accessible toilets, seating |

The design puzzle is dominance versus disguise. Sprinkler heads painted into ceilings. Exit signs integrated into decorative frames. Supply grilles punched into shadow gaps instead of slicing through ornament bands.

You will lose some original fabric to make these systems work. The question is where that loss hurts least.

Accessibility: not decoration, but structure

This is where many historic projects go wrong. A discreet platform lift hidden behind a staff door is not enough.

Accessibility is not an extra. It is part of the flow:

– Several wheelchair positions dispersed in the auditorium, not just in the back row.

– Companion seats integrated so people sit with friends, not in separate zones.

– Clear circulation without abrupt level changes.

– Accessible dressing rooms and backstage routes, so disabled practitioners can work there, not just watch from the stalls.

It will challenge your desire to restore every stair and terrace. Some historic stairs may need to be altered or duplicated. This is not failure. It is the building learning new manners.

If the most beautiful route through your theater is only available to people without mobility challenges, your restoration is incomplete.

Historical research vs. creative reinterpretation

How “accurate” should a restoration be?

You can hunt for old photographs, original drawings, paint scrapings, local memories. These are precious. They tell you what once was. But you are not obligated to rebuild 1912 exactly, with its ventilation assumptions, its social hierarchies, its sightline priorities.

You need to identify the core identity of the theater:

– Is it chiefly remembered for its lavish ceiling?

– Its unique proscenium?

– Its unusual balcony shape?

– Its marquee and street facade?

Those elements are your non-negotiable anchors. Around them, you have room to interpret.

For example:

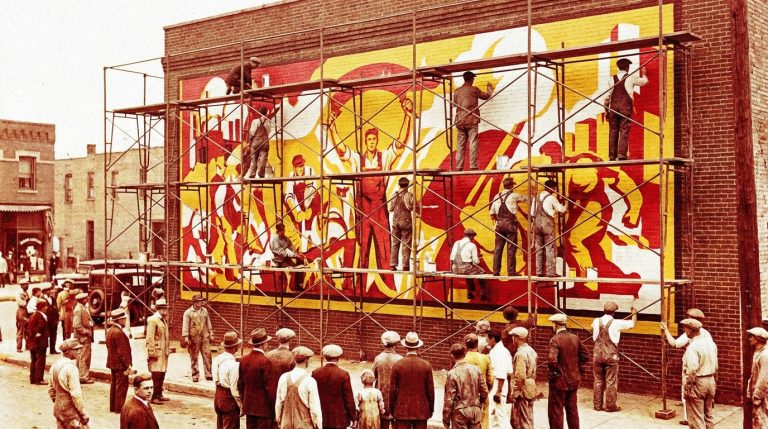

– You might bring back a lost mural program but choose contemporary artists to paint thematic “echoes” rather than direct replicas.

– You might restore a grand chandelier, but tune its internal lighting to modern color rendering and controllability.

– You might retain original timber and stone, but allow more minimal contemporary interventions where historic detail was already lost.

This is where bad approaches creep in: themed nostalgia that pastes on “old-time” novelties without understanding period proportions or materials. If your renovation starts to look like a stage set of a theater rather than a real one, you have gone too far into faux-history.

Programming reality: who will pay to be here?

Design for a fantasy season, and you risk an empty calendar.

Before you fix your restoration vs. modernization balance, interrogate your future use:

– Touring commercial shows need truck access, wing space, loading docks, and high rigging loads.

– Local theater groups need storage, rehearsal space, and flexible technical support.

– Event rentals need quick changeovers, catering access, and strong power for AV.

– Cinema use needs appropriate screen positions, masking, and projection lines.

If your beloved period balcony shape makes it impossible to project a film without cutting through a plaster wall, you either accept that you are not a cinema, or you adjust the architecture. There is no point in restoring a layout that cannot hold the programming that will keep the doors open.

The most beautiful restoration means little if the stage is dark five nights out of seven.

This is where modernization earns its keep: retractable seating for multi-use stages, flexible lighting control, strong rigging for varied set types, acoustic strategies that accommodate talkbacks one night and amplified bands the next.

Money, phasing, and the danger of “one big gesture”

A theater renovation is rarely a single project. It is a phased work of years. Here, a bad approach is common: spending most of the budget on a very photogenic lobby and ceiling, leaving backstage and systems limping along.

The more honest strategy is to tie each phase to both artistic and financial leverage:

– Phase 1: life-safety, structural repairs, minimal front-of-house refresh. Make the building safe and usable, even if not yet glamorous.

– Phase 2: technical and backstage modernization that unlocks higher-value programming.

– Phase 3: deep decorative restoration in audience-visible zones that builds public affection and donation value.

In parallel, decide where modern revenue anchors fit: a cafe that can operate on non-show days, rentable rehearsal rooms, co-working for creative businesses, a rooftop bar if the structure allows.

The choice between restoration and modernization is sometimes driven by donors. Some will give for naming rights on a gilded box, not for electrical upgrades. This can distort priorities if not managed.

Clear communication matters:

Be transparent about what money buys: not just beauty, but better work for artists, safer conditions for crews, and a more inclusive audience experience.

Materials, patina, and the right kind of newness

Old theaters wear their age differently. Some have lovely patina: rubbed stair treads, mellowed wood, softened metals. Others are simply decayed: water-stained ceilings, mold behind fabric, flaking paint that contains lead.

Your job is to distinguish between character and neglect.

Good restoration preserves patina where it does not harm people or structure. Handrails polished by decades of hands. Stone floors with slight dips. Timber with minor scuffs.

Good modernization acknowledges that some new interventions should look clearly new. A glass foyer extension that does not pretend to be original. A minimalist acoustic panel that is calm, not faux-ornate.

What to avoid:

– Plastic imitations of original materials.

– Over-smoothing and over-painting until the whole place feels like a reproduction.

If you hear yourself saying, “No one will ever know this was not original,” be careful. Erasing the distinction between past and present can make the building feel strangely inauthentic.

Working with regulators and heritage bodies

If the theater is protected, your choices will be shaped by listing status and local heritage rules. This can be a creative constraint or a frustrating limit.

Common tensions:

– You might need to justify any removal of original fabric with detailed documentation.

– New openings in facades or primary interior walls may trigger long approvals.

– Certain colors or materials might be restricted.

The trap is to blame everything on regulations. Many awkward renovations hide behind that excuse. Often, a more patient design process can locate hidden opportunities:

– Existing chases or voids where new ducts can run without cutting new holes.

– Redundant secondary staircases where lifts can be located with less impact.

– Non-original partitions that can be removed to reveal both heritage and useful volume.

Going in with an “us vs. them” mindset toward conservation officers almost always leads to lowest-common-denominator compromises. Treat them as another stakeholder in the building’s story, but do not be afraid to argue for the building’s continued life, not just its preservation.

Who leads: architect, theater consultant, or producer?

This is where your approach can fail quietly. If renovation is led purely by an architect without deep performance-space experience, you might get a visually elegant space that is difficult to use technically. If it is led solely by a theater consultant, you might get a hyper-functional box that undervalues historical and architectural nuance.

Ideally:

– The architect holds the whole spatial and visual story.

– The theater consultant defends function for performances.

– Acoustic, lighting, and heritage specialists integrate detail.

– The client or operator keeps reminding everyone: “We have to run this building day after day; how does this choice affect that?”

If everyone at the table loves theaters, but for different reasons, you are more likely to land on a renovation where restoration and modernization support each other.

Be wary of your own biases. If you, as a producer, are deeply nostalgic, you may resist necessary modernization that affects sightlines or capacity. If you are purely revenue-focused, you may undervalue the subtle magnetism of historic detail that draws people in.

Practical examples of balanced choices

To make this concrete, imagine a few common decisions and how a balanced approach might work.

Decision: original balcony front vs. better sightlines

– Pure restoration: Keep balcony exactly as is, accepting some seats with poor views.

– Pure modernization: Cut back balcony, replace with generic front, losing ornate plaster.

Balanced choice: Remove only sections that block critical sightlines; carefully detach and reposition plaster elements or cast new reproductions on a reshaped structure. Reduce seat count where views are unacceptable, but keep the balcony’s characteristic curve and rhythm.

Decision: historic chandelier vs. lighting flexibility

– Pure restoration: Fully restore chandelier, fixed, as primary house light.

– Pure modernization: Remove chandelier, replace with grid of downlights.

Balanced choice: Restore chandelier as centerpiece, but support it with perimeter and cove lighting for flexibility. Retrofit chandelier electrics for dimming and LED sources. Provide discrete rigging points above or around it for event fixtures, designed to disappear visually when not in use.

Decision: side wall ornament vs. acoustic treatment

– Pure restoration: Repair and repaint all ornament, no acoustic absorption.

– Pure modernization: Cover side walls with fabric panels, hiding ornament.

Balanced choice: Map acoustic trouble zones, keep ornament where it does not harm performance, integrate absorption in panels that follow original pilaster spacing and proportional logic, preserving at least some fields of original relief as intentional “breathing spaces.”

Knowing when to say no

Not every old theater should be rescued at any cost. Some buildings are too structurally compromised, too altered, too mis-sized for the intended program. Others sit in contexts where access and loading are unsolvable.

Saying no can be a form of respect. Turning a theater into housing, a market hall, or studios may be a more honest future than a forced return to performance use that never finds an audience.

Also, within a project, you should say no to certain design temptations:

– No to overloading walls and ceilings with “period-style” decor that never existed there.

– No to shoehorning in more seats than the comfort and codes allow.

– No to treating backstage as an afterthought because “the audience does not see it.”

A working theater is a living organism, not a photograph of itself. Restoration that forgets that is just taxidermy.

Renovating an old theater sits at the crossing of memory and possibility. Restoration and modernization are not opposing philosophies; they are two tools. The skill lies in knowing, for each inch of plaster, each row of seats, each unseen duct, which tool to pick up.

If you listen closely, the building will tell you where it wants to be polished back to former glory, and where it is quietly begging for a new spine, new lungs, a new voice. Your role is to give it both: a face that remembers, and a body that can perform again.