Fog clings to your ankles. The floor groans under your weight. Ahead, a figure is barely there in the dark, just a silhouette with eyes like wet coins. It turns toward you and moves. Too smoothly to be human. Too precisely to be a screen effect. Your heart does that small stutter where every sense snaps awake. Is that a live actor or a VR phantom learning how you fear?

That question sits at the heart of haunted attractions right now: do we wire guests into headsets and avatars, or keep investing in human performers behind latex and blood? The short answer: the future is not VR *instead of* live actors. The future belongs to attractions that treat technology like lighting gel on a spotlight: a color, a layer, not the source. VR, AR, and projection can stretch space, distort time, and shift perspective. Live actors still carry the emotional weight, the unpredictability, the eye contact that freezes people in a way circuitry cannot. The strongest haunted experiences will braid the two, with performers driving the experience and VR filling the cracks that human bodies and physical sets cannot reach.

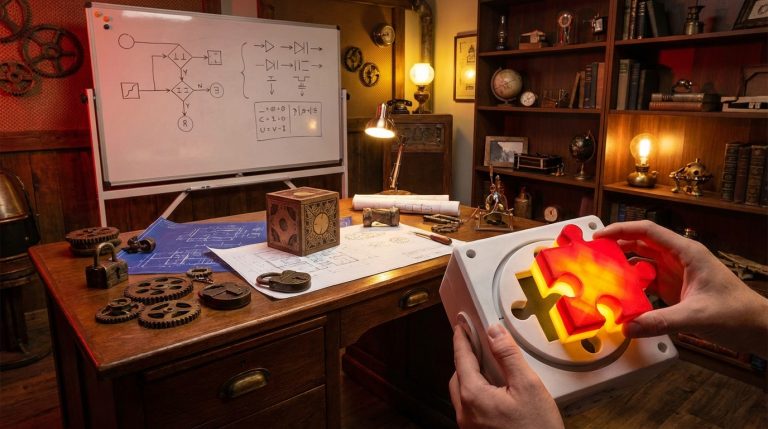

What VR Actually Brings To A Haunted Attraction

Before we talk about losing actors or saving them, we need to be honest about what VR can and cannot do inside a haunt.

- VR can shift the room around the guest: floors vanish, ceilings open, walls breathe, gravity lies.

- VR can repeat the same “scene” flawlessly for thousands of visitors without fatigue.

- VR cannot smell like damp concrete and fog fluid. It cannot brush past your sleeve. It cannot lean in and whisper your name wrong.

When I say VR here, I mean full-headset, 360-degree immersion. Not just projections. Not holograms. A guest’s eyes are inside a different world, while their body remains inside your physical footprint.

Picture a small warehouse, nothing glamorous. In the headset: a cathedral of rusted chains stretching into darkness, scaffolds dangling, wind howling through holes that do not exist. A conveyor moves guests forward. Live actors move around them in silence, tracking their positions, occasionally syncing moves with digital scare cues. Guests feel the motion underfoot, the gentle sway in their inner ear, the echo in their headphones. The physical space is modest. The perceived space is impossible.

VR is very good at:

| Strength | What it looks like in a haunt |

|---|---|

| Scale | Endless corridors, chasms, towering creatures without needing a stadium-sized building. |

| Impossibility | Gravity shifts, floors dropping away, rooms that flip upside down while the body stays safe. |

| Repeatability | Every showtime hits its cues exactly, lighting, sound, and visuals in perfect sync. |

| Branching paths | Guests taking different story routes without re-building physical sets. |

Where VR falters, and falters hard, is the lived friction of human presence.

Haunts are not only about what guests see. They are about the tension of being seen back.

Eye contact is the cruelest trick in a scare actor’s toolbox. A performer can track a timid guest through three rooms with nothing but a gaze and a slight head tilt. VR, even with eye tracking, still feels like a mirror hall of pixels. It responds. It does not watch.

The future of VR in haunted design will be strongest when we stop treating it as a “show in a box” and instead treat it like a flexible, corruptible lighting effect we can bend around bodies and live performances.

Live Actors: The Heartbeat In The Dark

Take away all the tech. Strip the haunt down to painted flats, a smoke machine that barely works, and a few $5 masks. If you still have committed actors, you can still terrify people.

A performer in a rubber mask can improvise around a group who did not react to a planned scare. They can shift tone on the fly. They can decide that tonight, “Room 7” is not really a scream moment; it is a dread moment, a slow burn, because the line outside is long and the guests are tired and need pacing.

VR can adapt based on data. Actors adapt based on instinct.

Here is what live performers deliver that VR will struggle to touch:

| Actor Power | Impact on guests |

|---|---|

| Improvisation | They can respond to names, jokes, fears, and behaviors in real time. |

| Physical presence | Sound of real footsteps, warmth of a body nearby, the sense of a real mass in the dark. |

| Social tension | Guests perform for actors, giggle, overact, or freeze. That social energy amplifies fear. |

| Mistakes | A stumble, a laugh, a broken line that turns into something stranger and funnier or scarier. |

Guests might say they want “the craziest tech,” but what they re-tell at work next week usually centers on a moment of interaction. The actor who followed them half the maze, never blinking. The creature that said their full name in the wrong voice. The character who comforted a shaking friend, then turned on them with a knife scrape and a perfectly timed roar.

Good haunted attractions are live theater in disguise. Sometimes in bad makeup. But still theater.

So the question is not “VR or live actors?” The question is: where does human presence carry the story, and where does technology extend what bodies cannot do?

VR-Heavy Haunts: Where They Shine And Where They Break

Let us imagine a haunt that decides to go all in on VR. Guests line up. Staff fit them with headsets, maybe haptic vests. They walk through a path marked by physical rails, but what they *see* is a crumbling asylum in a storm, with spirits tearing through walls and neon ectoplasm dripping from the ceiling.

This model has a certain appeal: less building, less scenic labor, easily re-skinned each year with new files. The show is consistent. You can export it to other locations and keep the experience similar.

But there is a tension here that you cannot code away.

First: the bottleneck. Headsets require fitting, cleaning, charging. You cannot simply push guests through like a conga line. The capacity is fragile.

Second: the hygiene and comfort factor. Many guests do not like wearing shared gear on their face. Some get motion sick. Some wear glasses that never quite fit under the hardware.

Third, and more important creatively: if everyone is inside their own personal screen, the group experience starts to thin. A lot of haunted fun is the echo of someone else’s scream, the way fear cascades from the bravest friend to the most nervous.

You can simulate other avatars in VR. You can design shared scares. But the quiet meta-theater of watching your friend slowly get more uncomfortable is lost when both of you are blindfolded by pixels.

The more equipment you put between guest and space, the more you must fight to keep the experience feeling human, not gadget-driven.

This does not mean VR-heavy haunts are a mistake. It means the creative strategy has to accept the medium’s limits.

A strong VR-forward haunt leans into sensations that only virtual space can deliver:

Impossibility As The Main Actor

If the star of your haunt is a demon clown with a chainsaw, VR is the wrong throne. A physical clown screaming in your face will always be scarier.

But if the star is a looping stairwell that does not end, where every step you take is reproduced in perfect, disorienting symmetry, VR wins. If the star is a feeling of the floor turning liquid around your ankles while your body stays on a firm platform, VR wins.

You design around uncanny physics, not costumes. Around perspectives, not close-ups.

Avatar Threat Instead Of Human Threat

In VR, your “villain” must feel anchored. A floating model that jitters slightly on a head turn will never feel like it can hurt you.

So you lean into abstract menace. Shadows. Swarms. Impossible creatures that wrap around the entire field of view. Environments that shift personalities: a room that watches you, follows, repeats your movements back at you with a delay.

Actors here, if present physically, become guides and safety anchors: people who help guests in and out, perhaps speak in character while you gear up, or stand near certain sections to physically touch or move guests in ways that sync with what they are seeing.

Live-Actor Haunts: Where They Struggle Without Tech

There is a common romantic idea: throw out screens, throw out LEDs, and just put human beings in rooms. Let the craft of acting and scenic carry everything.

That can work, especially in intimate, story-heavy haunted experiences. But there are limits, and pretending they do not exist is not responsible design.

Pure actor-based haunts wrestle with:

Repetition And Fatigue

An actor screams the same line 400 times in a night. Muscles strain. Voices go. Timing starts to degrade. The ninth group at midnight does not always get the same spark the first group did.

VR never loses its voice. Sound design plays the same way every time, with the same emotional cadence.

The fix is not VR replacing the actor. The fix is layering. Use lighting, sound, and subtle automated flourishes to carry load so that your actor can do what only a human can: choose moments, not constant noise.

Space And Budget

Big creatures, collapsing rooms, endless corridors: those are expensive and need square footage. Too many haunts solve this with the same repeating design: narrow hallway, hidden boo hole, strobe, scream. Repeat.

Here is where certain tech tools help without taking over. Projections can extend a room. AR through small handheld devices or glasses can overlay an extra layer without fully removing guests from the physical set. Pepper’s Ghost and similar illusions can spawn apparitions where there is no space for more rooms.

You do not need full VR to stretch reality. Sometimes a single, skillful illusion in one room does more than an entire headset segment tacked onto a haunt that does not need it.

Technology should support your actors like a good set supports a lead performer: giving them context, never stealing the entire frame.

Hybrid Haunts: Where VR And Actors Actually Sing Together

The richest future for haunted attractions sits in experiences that treat VR like a single chapter inside a live, actor-driven story.

Imagine this path:

You begin in a real room. An intake ward. Fluorescent tubes that flicker in that ugly beige tone that drains all color from faces. A nurse in spotless white speaks to your group gently, checking names against a clipboard. Her voice cracks once, almost imperceptibly.

She tells you the hospital is closed now. All staff removed. But there is an experiment still running in the basement, and you are here as “monitors.” She leads you down a real hallway that smells of bleach and plastic curtains. You hear distant hums, low and mechanical.

At the end, another staff member, quieter, instructs you to put on headsets. The story is simple: you will “see” what the last patients saw.

Into VR you go. The walls warp. The nurse’s face decays. The coordination between the physical room and the VR feed makes your body uncertain. Floors tilt that are perfectly level in reality. Hands reach for you in the headset but never touch.

Then suddenly: blackout. The headset dies. Staff rush in, not acting this time, just very practical, pulling gear off. “We lost power, we need to move you,” they say, leading you through the real building, no VR, no illusions. Only now the hall is changed. Lights are red. Doors that were closed are open. And human actors, not pixels, move in the periphery.

In this hybrid design:

– VR handled the impossible. Distorted bodies, floating furniture, walls that bled.

– Live performers handled trust, unease, the feeling that something was wrong *even before* the visible horror.

– The shift between them created a jolt that no single medium could manage.

The future of haunted design is full of these transitions. Where guests are not locked into a headset for 30 minutes, but instead dip in and out of digital layers while the core journey stays grounded in physical rooms and embodied characters.

Cost, Maintenance, And The Unromantic Side Of The Future

Artistic visions aside, every creative director has to live with budgets, maintenance headaches, and staff training.

VR is not cheap. Headsets break. Lenses scratch. Firmware updates go wrong. Battery life shortens. You need tech staff on site, not just stage managers.

Live actors are not cheap either. They need training, management, costumes, makeup, breaks, support for injuries and burnout.

The cost argument that “VR will replace actors and save money” is shallow. The money does not vanish. It shifts.

You are trading human labor for hardware upkeep and software development, not removing the need for care and attention.

For many mid-size attractions, the best path is a controlled, contained use of VR:

– One strong VR room or segment, heavily themed and tightly operated.

– The bulk of the haunt carried by scenic design, lighting, sound, and performers.

– A seasonal update cycle where VR content can change more rapidly than sets.

That allows experimentation without risking the entire experience on a fickle hardware pipeline.

Audience Expectation: Who Actually Wants What?

Different guests crave different flavors of fear.

The Tech Enthusiasts

Some guests want the novelty of VR. They want to feel like they are inside a horror game. For them, headset segments are a draw, even if they know the scares are simulated.

They often care about visual spectacle: large monsters, spectacular environments, unusual motion effects. They are willing to forgive a bit of artificiality in exchange for scale.

The Purists

Others feel safer in a headset than they do in a hallway with a live actor. They know, deep down, that they can always rip the gear off and step back into the queue.

What truly unnerves them is a real person in a mask standing too close and not breaking character. They want intimacy, narrative, eye contact, not necessarily big effects.

Designing for both at once is possible, but you must be clear about what your show promises. Advertising pure “VR horror” and then delivering mostly actors will upset one group. Advertising a “live haunt” and forcing guests into long headset sequences will upset another.

The future looks brightest for attractions that are honest in their marketing about the mix, and that use VR sparingly, as a highlight, not a crutch.

Safety And Consent: VR vs Live Actors

Both mediums carry different risks.

With VR:

– Disorientation can cause trips and falls.

– Some guests experience simulator sickness.

– Blindness to the physical environment makes emergency response trickier.

With live actors:

– Jump scares can cause panic runs, collisions, and accidental hits.

– Physical proximity can trigger trauma for some guests.

– Misread social cues can turn playful interaction uncomfortable.

VR gives you fine control over visual intensity. You can turn a monster down, adjust timing, throttle the number of stimuli. Live actors require clear training, boundaries, and protocols.

A mixed approach to safety is clever design: let VR carry the more visually extreme content where the body is secured, then let actors handle lower-intensity but more emotionally layered interactions when guests are fully aware of their surroundings.

From Haunted House To Haunted Ritual

Beneath the costumes and the code, haunted attractions are controlled rituals of fear. Guests consent to be frightened inside a safe container. They step out, laugh, and feel lighter.

This ritual quality is where live actors shine. They open the door, welcome you, lock eyes, set the rules without you feeling rules at all. They can adjust energy on the fly.

VR changes the ritual. Headsets are like masks worn by the audience. You cover their faces, you take away direct eye contact, and you ask them to trust the system more than the human.

Used without care, VR can break the ritual’s delicate exchange: “We scare you, but we see you.”

Used thoughtfully, VR becomes another mask in the ceremony. Put on in one room, taken off in another, like moving through different phases of an initiation: the blindfold, the trial, the reveal.

The future of haunted attractions will belong to creators who think like ritual designers, not gadget collectors.

VR will sit alongside animatronics, projection, scent machines, air cannons, and hidden speakers. A tool among tools. The living spine of the ritual, though, will stay human.

Humans lead you in. Humans watch you shake. Humans stand at the exit, silent, as you laugh too loudly and insist that you were not really scared.

If You Are Designing Now: Practical Creative Choices

If you are currently sketching a new haunt or planning to upgrade an existing one, you face real decisions: where to put your time, money, and emotional energy.

I would challenge a few instincts that are common:

Do Not Build A VR Segment Just Because The Hardware Is On Sale

A VR room without a strong narrative reason to exist will feel tacked on. Guests will sense that it is the “sponsor tech” area, not the heart of the show.

Ask yourself: what can happen in VR that absolutely cannot happen in my physical build, and that serves the story or theme? If you do not have a sharp answer, stay with practical effects and actors.

Protect Your Actors From Becoming Button Pressers

There is a risk in hybrid haunts: performers are pushed into roles where they mainly reset props, manage VR gear, or press cue buttons while the real “show” happens on a screen.

That is a waste.

Design scenes where actors have agency: they decide whom to target, when to hold silence, when to calm a scared guest, when to turn gentle horror into comedy for a moment. Let the tech automate the background, not the foreground.

Build One Excellent VR Moment Instead Of Five Mediocre Ones

Guests remember peaks. One unforgettable ascent into a digital void will linger longer than a series of small headset interludes that all feel the same.

Concentrate detail into a single VR centerpiece that your marketing can honestly highlight: “the elevator that never stops,” “the corridor that loops on itself,” “the mirror room that learns your face.”

Let the rest of the haunt breathe with human presence.

Where This Seems To Be Heading

If you stand back and look at the current trend, you see three lines forming:

1. Pure live haunts refining their craft, investing in actor training, narrative, and richer scenic detail instead of leaning on screens.

2. VR arcades and VR-only horror experiences treating fear like a game level, with very little live interaction.

3. Hybrid haunted experiences finding the middle, letting actors and VR alternate control of the guest’s senses.

Over time, I expect the second category to feel more like gaming and less like haunted theater. The first to deepen into something closer to immersive drama with scares. The third, if done with care, will feel like a new kind of ritual: flickering between worlds, grounded by real people.

The question is not whether VR will replace live actors. It will not. The question is whether we allow the efficiency of code to flatten the messy, fragile, irreplaceable presence of human fear and human play.

A future haunted attraction that moves people will still need someone in a mask or makeup, somewhere in the dark, holding just a little too much silence before they take a step toward you and say, softly, in a voice no speaker has ever reproduced correctly:

“I have been waiting for you.”